We spoke with Noju Studio

An interview with Eduardo Tazón, to talk about Studio Noju, an intuitive and sensitive architecture studio that understands design as a broad creative field, applicable to multiple scales and disciplines.

The English words not just are the origin of the name of this studio founded in 2020 by Antonio Mora and Eduardo Tazón. They chose them because their meaning not only reflects their desire not to limit themselves to a single discipline, but to combine all of them in a fluid way. Without starting from previous concepts and letting each project speak for itself, they sign from new construction and rehabilitation works to product design, exhibitions and interior design. Casa Triana was the key project that discovered their creative compatibility and theirs is a work as round and photogenic as the rehabilitation of a duplex in an iconic building. So much so that it is Torres Blancas by Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza, a turning point in their career and a work that has transcended the concept of home and now they repeat the experience to rescue another project from the sixties and make it their own because “the best client is oneself”.

From their beginnings in New York, they have embraced interscalability and are celebrating five years of career seeing how their work occupies the pages of the most important specialized publications.

We talked to Eduardo Tazón about their way of working, upcoming projects and a dream to fulfill.

What does Studio Noju mean?

Noju stands for Not Just, and it comes from the idea that we didn’t want to limit ourselves to a single discipline. It’s not just architecture, it’s not just interior design, it’s not just product design or decoration. That breadth is precisely what defines our approach.

It all started when we were living in the United States. Antonio opened an Instagram account simply to share references that inspired us. Without much intention at first, we were building our own imaginary, made of things that we liked and that somehow began to set the course of what we wanted to do. That’s how the seed of the studio was born.

The name Noju fit very well in English: short, sonorous and with that implicit meaning of amplitude and creative freedom.

What are the beginnings and how did the studio originate?

Well, my partner in the studio is also my partner in life, so, basically, the origin of the studio is also born from that personal relationship. In 2015 we went to live in the United States. I went to do a master’s degree at Columbia University and shortly after that he also moved to New York and started working in a Spanish architecture and interior design studio.

After finishing my master’s degree, I went through several studios and towards the end of our time in the U.S., the situation with visas became a bit unstable – every year was like Russian roulette – so we started to consider, “Okay, if we had to go back to Spain, would we set up our own studio?”

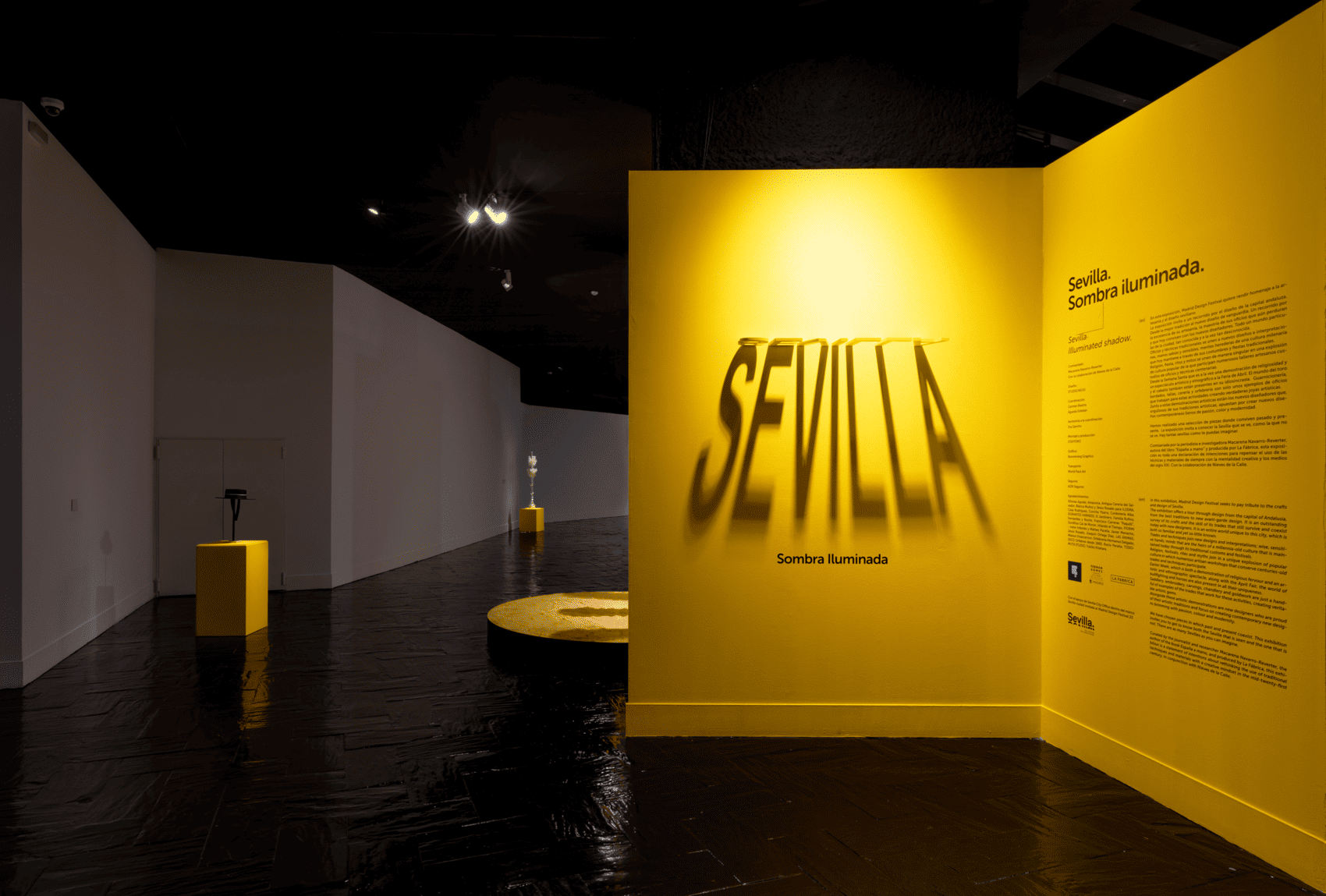

And, interestingly enough, it all started before we even came back. We had our first long-distance commission, which was the renovation of an apartment in Seville – Casa Triana – and we did practically everything by video calls and WhatsApp. We didn’t think of it at the time as “our first studio project”, but it was the first time we worked together directly, sharing ideas, seeing how our sensibilities intersected, and it worked very well.

Until then we had never worked together, so it was also a kind of experiment. He’s from Seville, I’m from Madrid, and since then the studio has been maintained with that kind of dual headquarters between the two cities.

After Casa Triana, we decided to return definitively to Spain in 2019. A few months later, the pandemic started and it was like a forced restart, but also an opportunity to stop and rethink well what we wanted to do as a studio. At first we had in mind a project more focused on hospitality, something more entrepreneurial perhaps, but everything ended up evolving into what we are now: a creative studio with a very open approach.

What is your manifesto, your philosophy?

Actually, we believe that one of the most important things nowadays is not to have a closed manifesto. Sometimes we even prefer not to have one at all. We are interested in each project having its own language, its own expression. We try not to impose a preconceived idea, but to let the project itself speak to us, to ask us for things.

For example, in the case of Torres Blancas, everything came from the building itself, from how it spoke to us and what it asked of us. So not having a rigid philosophy has allowed us to be more permeable and sensitive to the environment.

Obviously, it is impossible to work from a completely blank mind – we are not Zen monks – but we do try to maintain a certain mental and intuitive freedom when approaching each project. It is very difficult for us to rationalize our approach to design beforehand. Rather, it is a posteriori, when we see a finished project, when we begin to realize the connections, the coherence between one and the other. Sometimes it’s other people who point this out to us, and we find that fascinating.

What is the creative process like for Studio Noju?

We believe that design has a lot of intuition. And it’s important to let that intuition run free, without tying it down with a list of principles or fixed rules. We prefer to let that intuition guide the creative process, rather than rationalize it from the start.

There is also some study and trained sensibility. Whenever we approach a new project, especially in architecture, we investigate where it comes from, what the original architect wanted to do, what his intention was. That sensitivity -which we could not explain how it is acquired or how it is trained- is what, in a way, pulls the project forward.

And, although after the process we can look back and understand certain decisions from a rational point of view, we really like that along the way there is room for improvisation and freedom. This, curiously, is the opposite of how we were taught to design in school and in the master’s degree. There everything was much more methodical, more theoretical. This process has been, in a way, to relearn from scratch, to understand how we want to work on our own, without responding to the expectations of a teacher or a studio manager. Starting with your own blank sheet of paper and asking yourself: what really works for me?

How do you see these first five years of trajectory?

Five years in the world of architecture is still a very short time. Within the pace at which this discipline moves, a studio is still considered young even with ten years of experience, because the processes -both creative and construction- are much slower than in other areas.

That has also helped us to lower the pressure a bit. We don’t have the need to be “fulfilling chapters” or reaching certain milestones by force. If after five years we have not done such and such a thing, nothing happens. This is to be expected in our field.

Instead of being obsessed with an accelerated career, we prefer to take the time necessary for each project to make sense, to build something solid, with coherence and identity.

You work at different scales, what do your projects have in common?

I wish we could give you a clear line, something that exactly defines our work, but we honestly don’t believe that there is a single formula behind what we do. Even so, there are certain elements that do repeat themselves and that, over time, we have seen that they are part of our language.

One of them, without a doubt, is color. For us, color has never been a subject that scares us, on the contrary. From the beginning, we have been interested in going beyond the more neutral canon of white, beige or the raw tones that dominate so much in contemporary interior design. It’s not that we don’t value them, but we wanted to find another way to build a visual identity. And it shows. Color, for us, is not just an aesthetic or fashion resource, but an expressive and conceptual tool that we use with intention.

Do you give importance to materials?

We are very interested in understanding what a material can offer beyond the finish. What kind of geometry it generates, what volume it creates, how it behaves at a constructive level. We don’t see surfaces as something flat or simply decorative, but as elements that can have depth, texture and their own weight. That is why in many of our projects there are lattices, ceramics, walls that go in and out… We like architecture to have body, to be able to be read in layers.

There is also a coherence in the creative process, regardless of the scale. Over the years we have signed very different projects: from housing to offices, from product design to new architecture. And although the programs change, what doesn’t change is the way we approach each one: with the same care, the same kind of eye and the same interest in exploring.

It is true that the sector often pushes you to specialize: “focus only on residential”, “do only offices”… But for us, the enriching thing is to be able to work in different contexts. Applying a common sensibility to different challenges, and seeing how that identity adapts, transforms and grows with each project.

What is it like to renovate an apartment in a building as iconic as Torres Blancas, which is also your home?

It gives a lot of respect, to be honest. As soon as you face the project, you start to hear those critical voices that are very protectionist with the architectural heritage. They tell you that the ideal would be to leave everything as it was 60 years ago, and of course, that imposes.

But the truth is that we found ourselves with an apartment that had already been transformed, like many others in the building, and not always successfully. For example, many terraces had been closed. In the past, the number of rooms was valued much more than the square footage or outdoor space. Having a beautiful, open terrace was less important than being able to say that the house had four rooms. So many terraces, which now seem like a luxury to us, were enclosed.

With the pandemic that has changed, of course. Suddenly, opening terraces makes all the sense in the world, and that has started to show in the building as well. When we started the renovation, we were faced with this duality: on the one hand, respect for the work, and on the other, the awareness that not everything that was original had value in itself. For example, the original floor was a fairly standard small floorboard, like the ones you can find in any apartment in Madrid. The finishes in the bathroom and kitchen were not particularly remarkable either. But what there was – and a lot of it – was a wealth of ideas, of references, of concepts that were both in the building and in the architect’s texts.

How do you deal with it?

That’s the interesting thing: that many things are not protected by Heritage. Yes, they tell you that you can’t touch the façade, the wooden shutters or the common areas. But nobody protects, for example, the amber light that filters through the pavement of the service areas, or the way you circulate through the house, that fluid character, without straight corridors, with soft curves that envelop you. All this is not tangible, it is not catalogued, but it is part of the soul of the building.

The attitude with which we approached the project was very intuitive. We didn’t rationalize as much at the time as we do now when we tell about it. In just one month we had everything defined and we were super faithful to the initial plan. We were so overloaded with references, ideas… because the building gives you everything. It is a masterpiece. You walk in and you start to see things that don’t exist in other places. The lobby, the curved shapes, the white color, the details… it’s like making an intuitive catalog in your head, which then surfaces when you design.

Was it a research project?

We also read Oiza himself, how he talked about his project, about what he wanted the home to be. And you realize that many of his ideas never fully materialized. Construction quickly became expensive, and the interiors had to be highly standardized so that the apartments would be salable.

So our attitude was always one of utmost respect for the building, the architect, and the project. But also with a very non-museum-like vision. We don’t believe a home should remain frozen in time. There are other buildings where that makes sense, but here we think the value lies in activating Oiza’s ideas, not in preserving materials for the sake of preserving them.

In fact, it was very interesting that the Contemporary Architecture Foundation invited us to participate in ARCA Meetings, a presentation on contemporary heritage. There were very diverse points of view, most of them very protectionist, perhaps due to generational issues. But it was wonderful to see that there are many ways of understanding heritage. And in our case, they took our work at Torres Blancas as a positive example of how a building can be intervened, renovated, and enhanced without betraying it.

Has this meant a turning point for you?

This project has given us, in many ways, a roadmap. Also on a professional level, within the studio. We realized that there’s no better client than oneself. And as an architect, being your own client is an incredible opportunity. It gives you a lot of creative freedom.

In that sense, we’ve been able to take more risks, explore more radical ideas, and take projects where we really want them to be. And that has made us think of self-promotion as a real way of working: intervening in spaces, transforming them from within, and giving them a new life… almost like real estate transactions, yes, but with a very clear desire to always work on unique projects.

Because, in the end, being involved in such special projects is a luxury. It’s a very rare privilege. And if you can do it more than once in your life, that’s incredibly lucky.

What’s it like to live in such a special house?

It’s a project from the 1960s, so it’s a significant challenge from the start. But the truth is that living there is surprisingly easy. It’s very easy to get used to such a unique place… although you don’t realize it until you go out and live in other spaces. Then you really notice the contrast.

The house works very well. Everything flows naturally. There’s a very strong sensorial experience: the materials, for example, the wood provides a lot of warmth, the spaces are semi-open, a lot of light comes in through the terraces… it’s a very cozy house.

And there’s something that makes it even more special: everything is very well done. There’s no part of the project that feels out of place, no corner that makes you say “this doesn’t fit.” Everything follows the same principle, and it shows. In short, it’s very easy to live in this house.

What’s it like to live in such a special house?

It’s a project from the 1960s, so it’s a significant challenge from the start. But the truth is that living there is surprisingly easy. It’s very easy to get used to such a unique place… although you don’t realize it until you go out and live in other spaces. Then you really notice the contrast.

The house works very well. Everything flows naturally. There’s a very strong sensorial experience: the materials, for example, the wood provides a lot of warmth, the spaces are semi-open, a lot of light comes in through the terraces… it’s a very cozy house.

And there’s something that makes it even more special: everything is very well done. There’s no part of the project that feels out of place, no corner that makes you say “this doesn’t fit.” Everything follows the same principle, and it shows. In short, it’s very easy to live in this house.

Who are your main references and inspirations, your teachers?

The truth is that our references have overlapped over the years, with the experience of living together, working together, and, above all, traveling together. I think travel is an undeniable tool for gaining references. You can have the best Pinterest board in the world, but there’s nothing like traveling. And lately, since we’ve been lucky enough to go to Japan a couple of times, we’ve completely fallen in love. The number of references you can draw from there is incredible: from the most traditional to the most contemporary.

Personally, I’ve always considered Japanese studios as my references. Although our work doesn’t have a direct relationship with them, there is a sensitivity, an elegance, a composition, and a connection with nature that has always captivated me. Even in more local works, I’ve been fascinated by their delicacy from the beginning. And although our way of appropriating those ideas may differ, the admiration and that sensitivity have always been present for me.

Nowadays, I think one of the biggest challenges is learning to digest the enormous amount of references we’re exposed to. It’s no longer just about reading a book or a monograph like The Croquis by an architect you admire. Now, the moment a project is finished in Australia, you’re already looking at the photos on Instagram. And that’s a challenge in itself: knowing how to select, filter, and digest that avalanche of images and information.

What’s your method?

In fact, in our studio, that’s one of the ways we communicate. When we start a project, ideas often emerge intuitively, without being clear about where they come from. And what I usually do is capture that first “cloud” of ideas on Pinterest or a similar platform, collecting references that are in line with what the project begins to suggest, without taking them literally. Sometimes it’s a painting, sometimes a sculpture, an interior, a work of art… anything that helps build that visual universe. And when I share that with Antonio, my partner, he can say, “Okay, I see where you’re going with this.” It’s not about copying anything, but rather honing a creative intuition and visualizing it in some way.

We think it’s essential to know where the references come from, who created them, and what their context is. That’s clear. But we increasingly feel less identified with the idea of having five favorite architects or artists to whom we constantly pay tribute. At least in our case, that’s not the case. We’re driven more by sensibilities, by intuitions, by connections that sometimes don’t even have anything to do directly with architecture.

Product design, exhibitions, office and residential projects… Do you consciously choose to approach different disciplines, or does it just arise?

For us, interscalability is fundamental. We don’t like to limit ourselves to a single scale or discipline. Sometimes, obviously, we can’t control what types of commissions come in, but we are clear that we don’t want to limit ourselves. In fact, we love changing scales! It’s almost like a muscle workout: if you haven’t used your left arm for a year, you suddenly decide to exercise it again. Changing scales works a bit like that for us; it reactivates other parts of our thinking and creative process.

When we work in product design, for example, we are faced with a completely different scale, with its own needs, materials, and possibilities. It forces us to deeply understand the raw material we are working with, its limits, its behavior… It’s a challenge we enjoy.

You also do educational work…

We’ve been teaching classes at the IED, in a master’s program in interior design, and the subject we teach is called Materiality. We’ve approached it from the idea of deeply understanding materials—ceramics, glass, wood—and then applying them to product design. With the students, we develop small projects where they design products from these materials, thinking about their application in interior spaces. Sometimes it starts with something small, like a ceramic lattice or a floor, and little by little it grows into an entire pavilion based on that material logic.

That exercise of changing scale and understanding the material you’re working with is something we’re passionate about. And although we haven’t launched a new, specific product design line since our last collection, we’re currently working on a fairly broad collection that ranges from lighting to small-scale office furniture.

In this project, we’re using 3D printing, which opens up a whole new world of possibilities. For now, we’re experimenting with PLA, a type of plastic filament derived from corn. We chose this material because it’s available in a recycled version, allowing us to explore more sustainable options. Our goal isn’t just to learn how to print well, but also to overcome the very distinctive aesthetics of 3D printing. We want to develop shapes, textures, and geometries that take this type of production to a different place, more expressive, more sensitive. The final result shouldn’t look printed, but rather something with its own identity.

What are you working on right now? Can you tell us about any specific projects or share any general ideas?

Well… to a certain extent, yes. Some things are still confidential, but we can share some of our current approach.

Right now, we’re trying to be more selective about the projects we accept. At the beginning of the studio, things were different: we were more open to any type of commission, budget, or scale. But now we prefer to do less, but do it better. Choose wisely, take the time, and put love into each project.

One of our most important current projects is a private home, which is based in a very unique context. The house dates from the 1960s and 1970s, with architecture very characteristic of that era, and we’re particularly interested in maintaining that original essence. It’s an exercise in both respect and reinterpretation, and we’re very excited about it.

At the same time, we’re returning to product design, with the idea of launching a new collection this year. It will be self-produced, because we’re interested in exploring the extent to which we can take on the entire manufacturing process in an almost self-sufficient manner. The idea is to minimize the production route, both for sustainability reasons and because we want more control over the process and the finishes.

And we’re still open to emerging independent projects with private clients, although many of these haven’t been announced yet. But yes, we’re in a consolidation phase, fine-tuning what we want to do and how we want to do it.

What’s that dream you’d like to fulfill that’s still yet to come?

There’s a dream we’re very clear about, one we take quite seriously, and we’re keeping our eyes wide open, waiting for the first opportunity to put it into action.

Since we returned from New York, we’ve been mulling over the idea of developing a hotel project in the landscape, with a proposal that combines architecture, restoration, and a carefully curated hospitality experience. It’s a field that fascinates us deeply. Whenever we can, we seek out unique hotels around the world, places that offer something different, with character, sensitivity, and a connection to the environment. And we’d love to bring something like that here, to Spain.

We believe that the world of landscape hotels in our country still has much to explore, especially from a more contemporary, sensitive, and architectural perspective. In fact, a few years ago we tried to do so. We spent almost a whole year searching for the right location: we explored sites in Extremadura, Catalonia, the Basque Country… Extremadura was one of the most promising options because the regulations on rural land were somewhat more flexible. But just when it seemed we could take the plunge, the pandemic hit. And with it, rural land—which until then had been more affordable—became dramatically more expensive because everyone wanted to move to the countryside. And at the same time, property prices in Madrid dropped for the first time in a long time… That’s when we made the decision to buy Torres Blancas, and we temporarily shelved that other project.

But we’re absolutely clear that, sooner or later, we’ll do it. It’s not just an idea thrown into the air; it’s deeply rooted in our minds, well thought out. We want it to be a place where we, too, would want to stay. An intimate place, with a maximum of 10 or 12 rooms, very boutique, deeply connected to nature, where you don’t feel like you’re in a hotel, but in a special, peaceful, immersive place.

And with a restaurant menu that’s up to par. Something powerful, well thought out, with excellent cuisine. For us, design, surroundings, and gastronomy have to go hand in hand. That’s the experience we want to create. And hopefully we’ll soon find the location and the conditions to make it a reality.

Written by: Beatriz Fabián

Beatriz is a journalist specializing in offline and online editorial content on design, architecture, interior design, art, gastronomy, and lifestyle.