Carlos Garaicoa, a global artist

We talked to the Spanish Cuban artist Carlos Garaicoa about his beginnings, his way of working closely linked to literature, whose creations drink from many different disciplines to offer a consolidated work where the conceptual invites us to reflect on the environment in which we live.

The protective spirit of a place, in particular, the genius loci of contemporary cities underlies the work proposed by this Cuban-born artist who has been living in Madrid for almost two decades. Carlos Garaicoa (Havana, 1967) expresses his interesting sum of life circumstances, experiences and personal knowledge through multiple media and disciplines, from sculpture to photography, drawing and installation, painting but also architecture, urbanism and writing. He defines himself as a conceptual artist and his work focuses a lot on what can be expressed by the materials he scrutinizes before applying them. He thinks that “art is profoundly artisanal, it is an understanding of form, of material, of the very traditions of art”. He says that he has reached a point in his career where what he longs for is to have enough time to sit at his small table full of notebooks and blank sheets of paper to continue creating and devising things that bring something new. He has participated in the proposal entitled Thinking the City promoted by Art U Ready, an initiative of The Sibarist and we chatted with him at El Invernadero.

How were your beginnings, how did you get here, things that have inspired you, skills and attitudes that have helped you and inspired others.

The answer is very complicated because it is an accumulation over time of experiences, of trial and error. I started as an amateur painter because I didn’t study Fine Arts although I always had the restlessness since I was a child. I was surrounded by artist friends, I also took some courses but then I studied something related to physics.

It was while studying that career when I realized that I wanted to start painting and in Cuba in the Casas de Cultura I began to learn the rudiments. Then I spent three years in the army and kept insisting that I wanted to paint. In the end, I am basically self-taught as an adult.

I also have an important link with literature, something that comes from my father, a great reader, and my brother also very sensitive to music, so we were, let’s say, on the periphery of intellectuality. It was a place of seed. I entered late and in my generation there are artists like Los Carpinteros or Tania Bruguera who have a high level academic training, I was an outsider -many careers in art are made like that-, I really lived it as a personal need. I drew, painted and at the university they accepted me with the portfolio I had. At the university, what you already have are thinking professors.

That is why my work is so open because it is related to painting, to sculpture, it drinks from many places. I was learning the rudiments of photography, learning to draw better, I had to catch up with the rest. In the long run, I believe that it is not obligatory to have an academic formation but that it is a true desire, a very big discipline to achieve things, to develop a language with which you have to fight a lot. When I was at university I began to develop and discover many things, having a more literary background I leaned towards the more conceptual, towards photography, that’s where my path opens up, I discover the city while I’m at school and I work from certain urban patterns.

Can you say that your biggest influence is literature?

There is a part of my training that is literary because not having grown up in art school with artists around had to do a lot of writing and still mine is still a very narrative work. It is very attached to a lot of writers and it is also a work that drinks a lot from the contradictory, the word always occupies a very strong part.

Who are the figures that have influenced you the most?

In my case, more than teachers, they have been people you admire and at a given moment you have the opportunity to exchange with them. Artists I have always admired are Lázaro Saavedra and Flavio Garciandía, who were not direct teachers.

Did your career begin in Havana?

Yes, I studied between ’89 and ’94 at the Higher Institute of Art and in ’94 I participated for the first time in the Havana Biennial. We are a generation that left school quite early, I’m referring to Los Carpinteros, Tania Bruguera and Sandra Ramos. I had already done things in Germany, until 1995 when I came to live in Europe and with a scholarship I lived in Switzerland for a year. A year later I was already doing two exhibitions in New York and a residency in a gallery. In 1995, I also participated in the first Johannesburg Biennial, there was a very big process from Cuba, people were looking for you there, in the 90’s there was a great connection with the United States. In Cuba you have the opportunity to be really very strong because you concentrate on making art from a very early age, you study art all your life. It’s like a real profession. The context is very rich, you live in a very particular world.

You are a complex and very interesting figure in the Spanish art scene, if you had to define your work as an artist, how would you do it?

I consider myself a conceptual artist, if it can be categorized as such, but I really feel very curious about all forms of conceptualism seen from the contemporary world, not in the traditional sense of the word and thought. I am very attached to this movement because I was trained a lot from my beginnings doing that kind of work. In Spain I have discovered that I have always been very curious about the materials that have had a powerful path in my work. When I came to live here I also started to work with very complex associations. My conceptual interest with art has extrapolated into an interest also in how materials work in the work. Seeing how the material actually tells stories and can define concepts. It’s a very primal moment in the work. I consider myself an artist with my antennae on, I have no prejudices I started very strong with photography and writing, now I’m back to painting, creating assemblages in carpentry, I always do things that interest me and that’s why I’m a contemporary artist in every sense, I have no limits to what I can do.

Today you can do all things, the important thing is to know why you want to do it. You research the materials but it’s about sensitively finding how the thought fits into different forms and materials. I believe that art is deeply artisanal, it is an understanding of form, of material, of the very traditions of art. I also consider myself a sculptor at times, mine is a discourse about space, the space of the city itself.

At what point in your career do art and the urban environment merge? How does that spark come about?

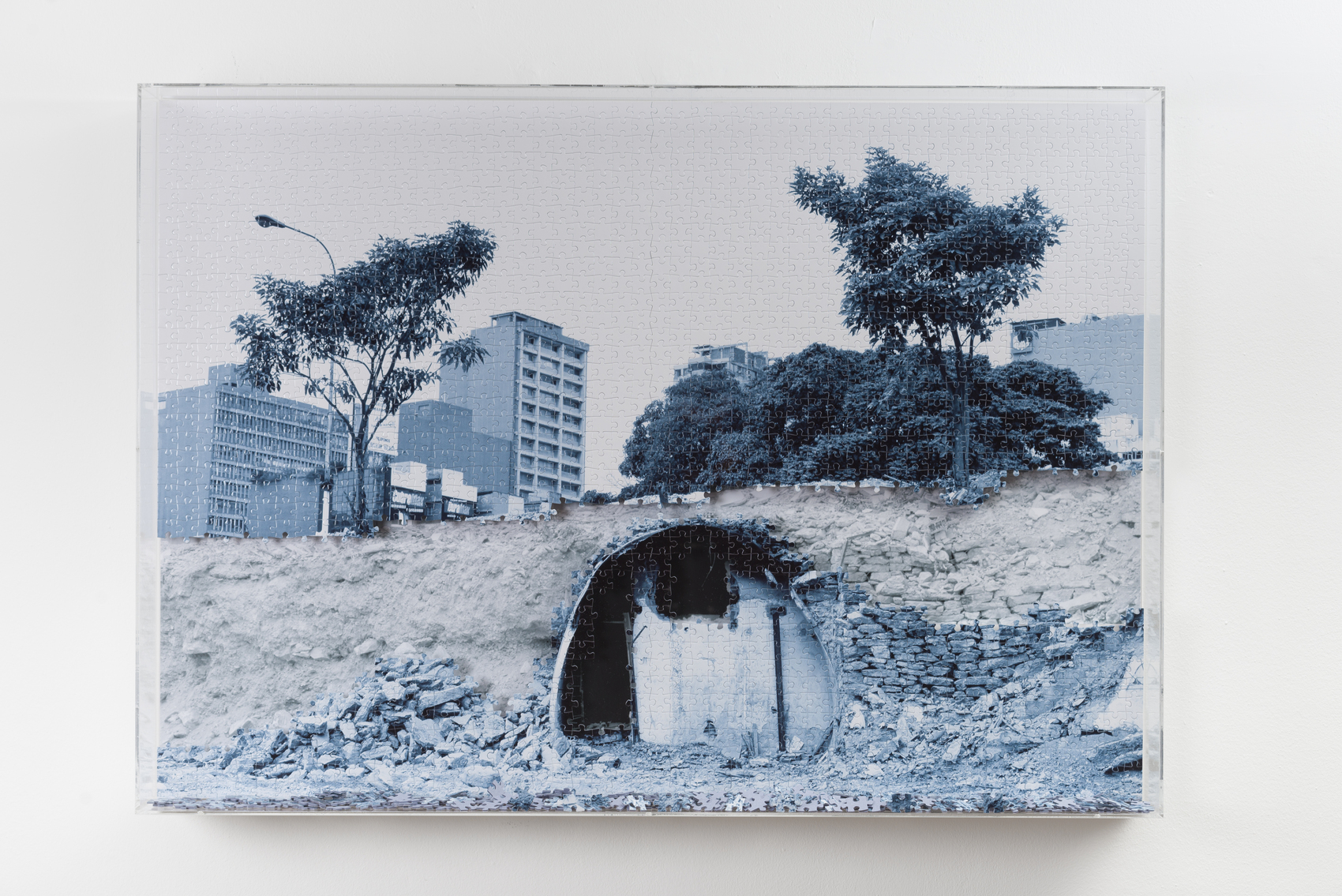

There has always been that spark because the urban environment is very present in my work from very early on. In the early 90’s I started doing things in the street, I discovered photography again because at home it had always been present. I grew up in Old Havana, a very rich and complex city that is architecturally marvelous, and from then on I decided to use it more as documentation and go beyond. My first work is to detect objects and numbers in the street, texts… That’s when I got closer to the city, I began to make drawings of the city as if I were an architect. My first madness in 93-94 was to invent buildings, it was a very funny time and from it there are many patterns that I make today. A lot of that has been transposed to objects in documentary photography. In 2010 I partnered with Factum Arte and thanks to them I created photographs in the form of tapestries, on stucco…

What is for you the genius loci of contemporary cities?

I think there is something in them that tells you things, they transmit a message. Not in all cities you can work, in some you feel that they don’t speak to you directly, however, with Madrid, New York, Sao Paulo, Havana you can connect. I’ve been very lucky because I’ve been invited to many places and I’ve been able to read and see the city and then say something, this became very fashionable in the 90s. The city was discovered in art in those years, before it was quite rare to make drawings of the city and quite unwelcome. From 96-97 the city begins to take a lot of strength in the art world and there is a radical change, everything has to do with architecture, projects are raised on the cities. There is something immanent in the cities that manages to welcome you to work.

What is it about these places that catch you?

They are extremely contradictory places politically, architecturally very rich, economically intense, they are forbidden cities. For example, I lived almost a year in the Swiss city of Biel-Bienne and I could never make a work, so I really felt that I had nothing to do there. I came to Holland, to Arnhem, and I found a model of the city and I saw how a small city where something so big happened has a concentrated energy of history that allows you to talk about it. There is a certain mystery and a certain surprise in it, it is not that there is a manual that tells you this is exactly what it is. For example, about Madrid I did work before I lived here and I spent three or four years during which I did nothing. It took me time to change the context and feel that it was my city. It’s not only the city, there are many things around it, the history, the politics, the economy? Wherever I go I do research, I read books, but sometimes even with books I can’t get to the heart of that place. The relationship between art and architecture is here to stay.

Sculpture, photography, drawing, installation, architecture, urbanism… Working in different media and disciplines, how do you manage to combine them all and with which medium do you feel more comfortable? Is there any medium that transmits better than another, why?

I work a lot with photography, I don’t travel with a camera, I’m more of an observer and I take photos when I need to, but I base a lot of my work on documentation, which doesn’t have to be photographic but historical. As I come from painting, I worked a lot with photography, then with drawing, very early I realized my relationship with sculpture and began to restore and recover objects, create fictions through those objects, installations with stones, with a Japanese door, in the end, the way I work today is very hybrid. When I decided to work as an architect I realized that I didn’t know how to do it, but I did it and I improved by drawing a lot. At the moment, I don’t look for a material for a work, I do things, I draw a lot in notebooks where I constantly draw the ideas I have in my head, whether they are sculptures or materials. I have referred a lot to materials that reflect the fragility of what I am talking about, for example, I have dedicated time to thread, paper, photography with thread. In the end, drawing and photography are my primary tools. The ability to think about materials is very open, sometimes I have ideas that are forms, I believe in a methodology that tells you where to go. I have no prejudices and I have learned to do, it is a lifelong learning, especially if you want to do different things.

When I talk about materials I work on any support, glass, metal… but in the end contemporary art is based on knowing how to use the resources at hand and today there are many technological resources that can help you. I love that, expanding my territory. Through photography you can do many things, in the studio you can do all kinds of crazy things, for example, I discovered that you can make photographs transferred to polystyrene, ten-meter tapestries from your photos, etc., you realize that you can do a thousand things.

Your works can sometimes seem intriguing or questioning to the viewer, what are your sources of inspiration? How is your way of working?

In my studio in Carabanchel I had a car workshop, a carpenter on the other side and I was with my drawings and I decided to make them in relief, I conveyed to them what I could do and in this way I found a hybridization of works and crafts that come together in my work. It is the proof that I don’t really have a precise plan, I have the perception that it can work, you have the ability to abstract to see if it will work. It’s a bit like working by trial and error. You are making the work in different places and they are making themselves, until you see them exhibited you don’t see how they have been changing. I control the space, how to adapt to it, to see what is left over and what is missing in a place.

You’ve been living in Spain for years and you work between Madrid and Havana. How does that mix work in your brain and how do we see it reflected in your work?

I never stopped having a studio in Cuba, I still have it, because I came in 2007, I had been in Brazil and had had attempts to be in other places like Switzerland and the United States. I’ve always had that nomadic thing, especially living on an island, where you always want to leave. Then there was the complexity of leaving Cuba which has all kinds of political and economic issues and all that the country as such implies. In 2006, when I traveled to Brazil, I had already created a studio and done important projects from Cuba, such as Documenta and the Venice Biennial. Then I faced the dilemma of dismantling a good and loyal team that knows, composed of art historians, architects, model makers, designers, real professionals. I decided to leave it so I have never divorced from Cuba, many of them are still with me and it is a long-distance collaboration.

After years I decided to set up a small institution called Artista por Artista, which was a point of professional, intellectual and personal rapprochement with Cuba. I also have a good team in Madrid in a studio in Carabanchel opened two years ago and designed by architect Juan Herreros. For me, who am from Old Havana, it preserves that deep neighborhood thing that has not yet been developed.

About thinking about the city, theme of the Art U Ready proposal, of which you are part of the jury, what is your perspective as an artist on cities?

Many cities are unfortunately losing essential things, because of the globalization that we have been talking about for some time now. It is becoming increasingly difficult to find something that is not a franchise, there is an economic overexploitation of the city that displaces much of its essence. That feeling of not being one hundred percent a neighborhood of Madrid and begin to see a huge resemblance between cities, it’s a shame. I am not saying that they do not grow, but we have to think about cities trying to understand how organic they themselves are. The citizen is not left the space to decide anything. Evidently, it must combine art, architecture and local thoughts without falling into provincialism. For example, in Carabanchel in five years we will be talking about another neighborhood. This displacement of the population because they cannot afford to rent or buy housing, is something very complex and the solutions must come from the central governments to, for example, build necessary housing or more social proposals.

To what extent can an artist help transform the urban environment from your point of view?

Artists have an essential role, what art does is to complexify reality, to understand it and make it more complex, more analytical and sensitive. Simply in this act, artistic thought and language are important because they are more cultured people, more knowledgeable and capable of transmitting to others. I don’t have to be sitting in a political forum, but discussing, talking and contributing ideas is how you draw attention to the city, to the ruins, to their fragility. Otherwise the city goes into an identity crisis. I see it in Carabanchel, as I saw it happen in Malasaña, when the logic that comes in is only that of big investments. I hope that this is the moment when governments come in to see that there are criteria to improve urban planning. Many things are going to happen in Carabanchel.

What are you working on at the moment?

I’m working on preparing a biennial to be held in September in Switzerland and also on a classical music festival in Italy. My wife, Mahé Marty, is a musician and is initiating the festival with a visual and sound work and I’m going to do an exhibition. Also the CAAC exhibition in the Canary Islands opens in Es Baluard in Mallorca which is very important and I am preparing a big project for the museum of the University of Navarra which is going to be done next year. In September the first report will be presented and it is a museum that I love.

What is your dream project, the one you would like to carry out or be commissioned to do?

I don’t think about those things, I have had the opportunity to do things, in England I developed an idea for a public library, I spent five years on it and it was never done. I consider myself a project developer. If they gave me a space X I would do something big for the city because I feel I have the capacity, but it is not something I would consider. Doing exhibitions is one’s dream, I dream too much, I have a desire to rest, not to do so much, every time you want more space and more time to dedicate to yourself, to be in your studio, to be reading. I like the exhibitions, now I have one at the Centro Atlántico de Arte Contemporáneo de Oiza and it’s wonderful, an incredible place. The work of the artist is to be constantly working and really as dreams are punctual you are invited to very important appointments but you think I do it professionally. Sincerely, without being modest, my main dream is to have new ideas that do not run out, to be able to keep dreaming and that dreams materialize in something new. With 30 years of career they ask you for a retrospective but I don’t like them at the moment because they make you old. I want to be able to continue sitting in my studio with my little notebook and see the works that you dream of materialize, that they are good things that have an impact.

What would you say to artists who are just starting out?

Discipline and work. If you really manage to discipline yourself every day and work, you get things done because that’s where you find answers. In my case, I don’t need much space, in my studio I have a table full of sheets and notebooks and I go there every day because when you start producing you can’t get distracted for a second. Picasso used to say “I don’t look for, I find” and that’s how it is, you have to work like him, all the time. I would tell him: find time every day to work, I see it in my family, they are all musicians and I believe that music is the most disciplined thing.

Editor: Beatriz Fabián

Beatriz is a journalist specialized in offline and online editorial content about design, architecture, interior design, art, gastronomy and lifestyle.