Interview with Boa Mistura

A talk with Javier Serrano of Boa Mistura, a collective of graffiti artists that has been creating murals for decades in more than 40 countries to generate changes in the territorial and social fabric.

This collective of artists who drank from graffiti and filled the asphalt of Madrid with phrases -Te comeré a versos was one of them-, have been creating murals since the end of 2001. They put their leitmotiv of the ‘good mix’ in public spaces in more than 40 countries around the world, collaborating with governmental organizations to focus on social issues, such as the UN, Amnesty International, Greenpeace, Cear, Action Against Hunger and the Red Cross. With their creations, they have participated in important events such as the Ibero-American Design Biennial, the Dakar Biennial, the Havana Biennial, the Milan Design Triennial and the ArcoMadrid fair. In addition to exhibiting at their main gallery, the Madrid-based Ponce+Robles, they have shown their work at the MAXXI Museum in Rome, the CAC Malaga and the ALT1 Museum in Seoul, among others. Germany, Manila and Serbia are the places where they are planning to carry out their next works. As they argue, the murals generate a story in the territory. Their creative work goes one step further. They began with the chimera of transforming the world, especially in the peripheries of the cities, and they lived it with certain pressure, now they take it in a calmer way. Here, Javier Serrano tells us about his 25-year trajectory as Boa Mistura.

For those who don’t know you, what is Boa Mistura?

A group of friends. We met in our neighborhood, Alameda de Osuna, painting graffiti in the late 90’s and, in 2001, we decided to give a name to that friendship: Boa Mistura. In 2010, after finishing our university careers we created the studio, formed by the Fine Arts graduates Pablo Ferreiro and Juan Jaume, the plastic artist Rubén Martín de Lucas, the illustrator Pablo Purón and the architect Javier Serrano. At present, the Pablos and I (Javier) are active, together with a great team formed by Javier Ballesteros, Jorge Muñoz, Camila Dorado and Jaime Pérez Lorenzo.

What were the beginnings like?

In November 2009, we were visiting Juan in Berlin, who was finishing Fine Arts at the Universität der Kunste. There we were painting daily for several weeks and, as part of that coexistence, we created a piece in front of the Berlin Wall, on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the fall of the wall, called “Die Umarmung” (The Embrace). That was the key moment that marked the beginning of our trajectory. We all agreed that we wanted to live like this and two months later, in January 2010, we rented an old ham shop in the Conde Duque neighborhood of Madrid. A small space where we met every day. And since then, we have not stopped doing it.

How do you analyze your evolution over these two decades since your founding in 2001?

Like all graffiti artists, we started spontaneously. Graffiti was our form of expression, of self-affirmation, of feeling that you were part of a larger collective that has its own codes. That motivated us individually, but over time, that motivation united us as a group and we began to put aside our individual egos to work collectively. We began to create pieces that sought to generate dialogues between us, a way of relating to each other that we have maintained to this day.

In 2011, we did an artistic residency in Cape Town (South Africa), an experience that marked us deeply. There we understood the importance of working in public space and the need to be respectful when intervening in it. It was a key change in our way of thinking. From that moment on, we began to work in a participatory way. It was the first time we involved other people in the creation of a mural and it was revealing. We saw how the painting not only transformed the places, but also the perception of the community living there, as they felt part of the process.

The most impressive thing you have experienced?

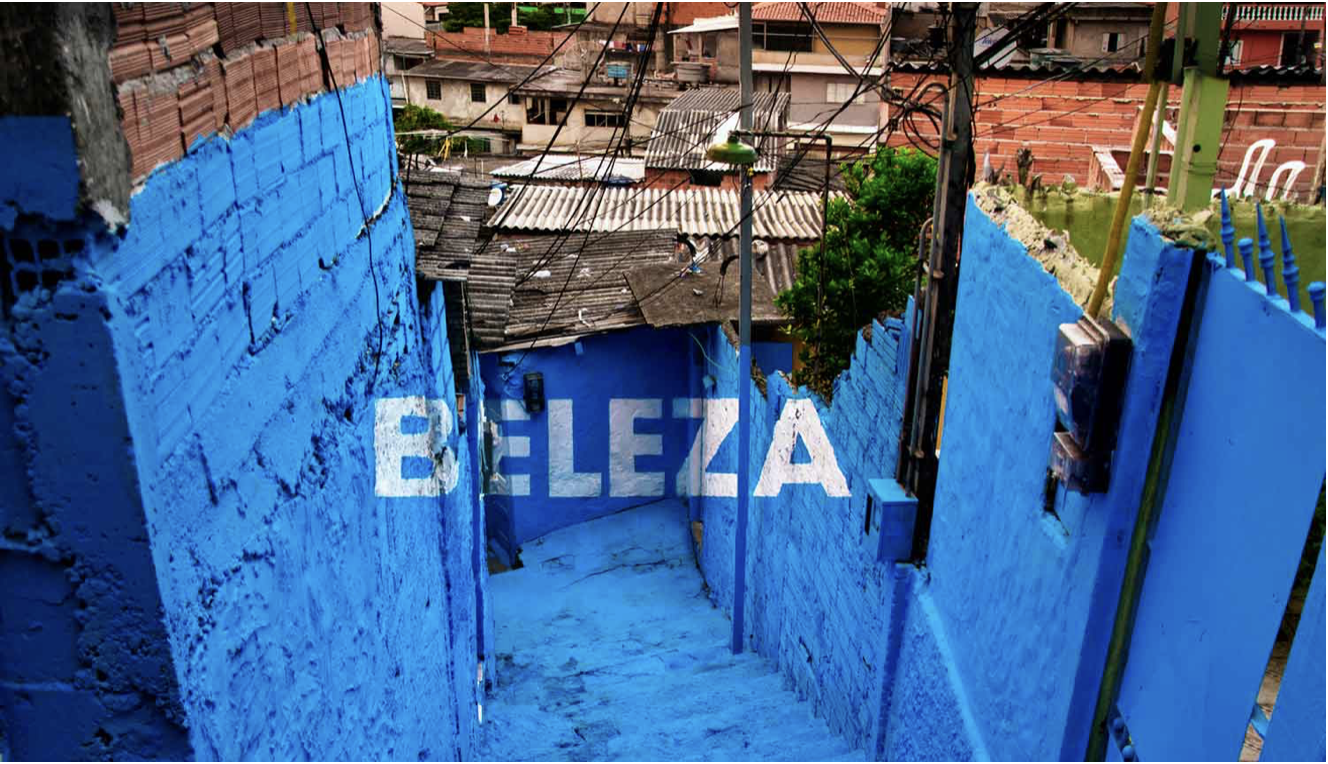

There is a project that is very little known, located in an Afro-descendant community in the Colombian Pacific: La Playita, in Buenaventura. It is a place marked by violence, where drug traffickers and paramilitaries fight for control of the port and, therefore, of a large part of the country’s wealth. Through the Sueño Pacífico Foundation, we were able to access the first pacified space in the city, a place where, previously, there were ‘casas de pique’, a methodology used by the armed groups to sow panic among the neighborhood that consisted of choosing a house at random and murdering the people who lived there. In this way they took control of the territory. It was a place with a lot of symbolic charge and great energy, because it was the first community that, organized, had managed to expel the violent ones.

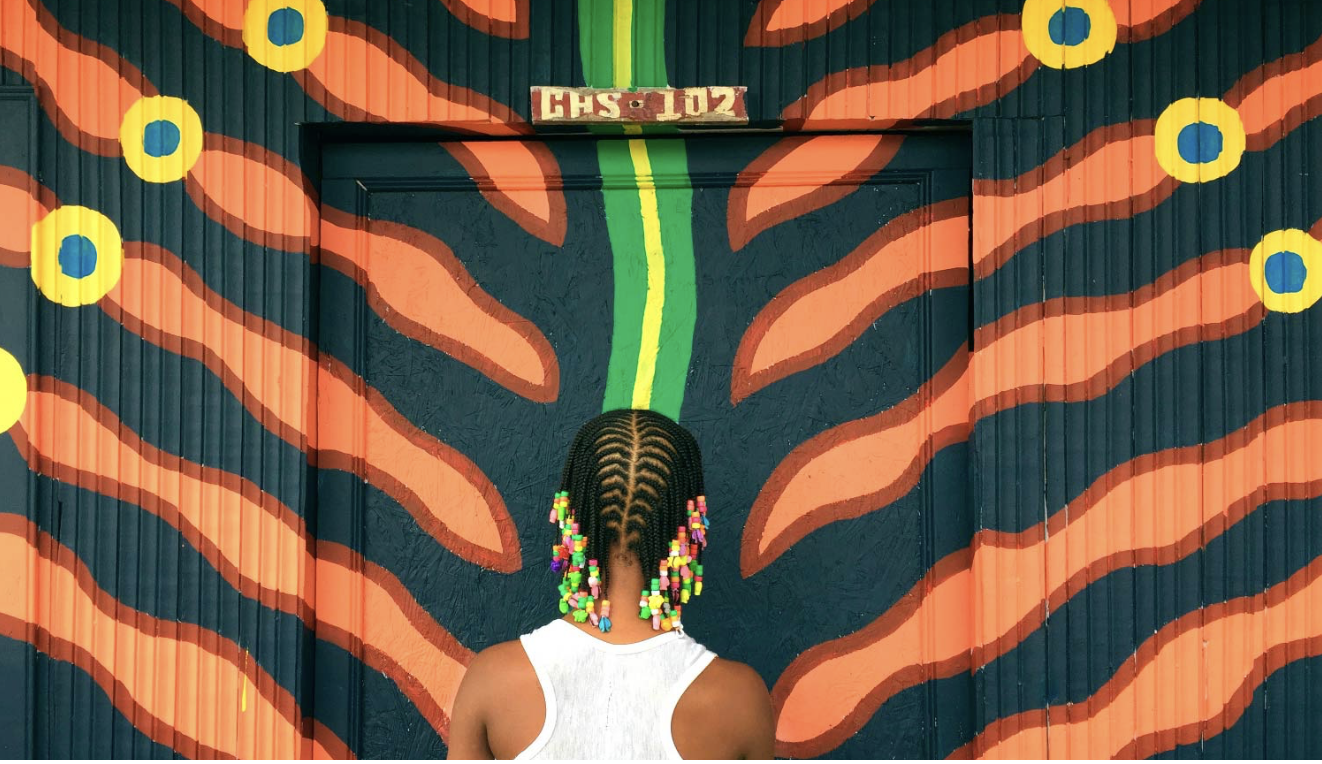

Working there, we were surprised by the spectacular hairstyles of the women and girls. One of the first days, some neighbors invited us to lunch and we asked them about the hairstyles. It was then that they told us that these hairstyles had a historical origin related to the escape during slavery. In those times, women wove their hair with escape routes to reach the palenques, the places of freedom. Thus, through the gesture of combing, they could escape.

We were fascinated by the way they used their hair as a means of encrypted communication and we decided to work with the shape of the hairstyles, to rescue those concepts and capture them on the facades of the houses. We created dynamics to graphically represent what they wanted to express, using braids and colored beads. The families of the houses we painted participated in the process: we would choose a concept, make the hairdo, paint it, and then take a picture. It was one of the heaviest and most beautiful experiences I remember.

You are always looking for the participation of the public…

Yes, it’s not just about arriving at a place and leaving our work. We work in specific places, physically anchored to a place. We can’t just take a piece from one place to another. We feel we have to respond to that context. It is something we have learned over the years by making mistakes because there have been times when we have arrived at places with a work that we thought was wonderful, previously conceptualized in our studio in Madrid and, once there, we realized that it did not make sense or connect with that space and, therefore, it was useless.

So, for us, the best way to connect is to understand the place through its people. That’s why we spend time living in those neighborhoods, to find a conceptual line that is in tune with what the inhabitants transmit to us. We create dynamics with the neighbors, we pose questions and activities to extract information from the place. In this way, we co-design with them, taking into account their aspirations, their desires, their expectations and opinions. Then, we take all that and process it through our plastic language.

In this way, the murals we create are more easily incorporated into the collective imagination, because they are born from there. As much as possible, we invite the inhabitants to also participate in the elaboration of the mural, which adds a playful and physical component to the process. When someone puts their effort, time and energy into a work, they feel proud of what they have created.

You have experienced in recent years a greater approach to the art world, why?

The pandemic impacted many aspects of our lives. We had to face the cancellation of almost our entire schedule for 2020 and therefore not knowing if we could continue to do what we had always done. Our projects involved public space, and you couldn’t go out; people engagement, and we couldn’t meet; and travel, and you couldn’t travel. It wasn’t until after the summer that we were able to make up a couple of commitments: an artist residency at the Centrequatre in Paris and a piece in Berlin with the Bauhaus Archiv. During the months we were locked up in our studio we began to investigate with pieces on mobile support. This allowed us to return to dialogue with each other in a more intimate way, without relying on external pacts as in the public space.

This is how we began to create pieces that can be collected and to awaken the interest of galleries that proposed us to exhibit these works.

And when everything was reactivated, we decided to continue with this line of research, conceptualizing hybrid projects, integrating public space and exhibition space. This is how Ubuntu, Re-Vs (Reversus) and Re-Act (Reaction) were born, where the role of the collector is fundamental in the definition of the project. All these works have been developed with Ponce + Robles, our mother gallery.

For example Ubuntu, which takes as its starting point the ancestral concept coined by the South African Xhosa, in which our individuality is only understood as part of a larger collective: “I am because we are all together”. That is why the project was born from a work divided into 36 parts, where each collector could acquire a single quadrant that would then be painted somewhere in the world. In addition to the acquired fragment, at the end of the project they would receive a photo of how that part of the work would look in another public context. In this way, the collector became a patron of a public work of art. Individual acts that add up to create something bigger. This project was awarded the OFF prize of PhotoEspaña 2023.

What was the last one, in Miami, about?

Re-Act is a project that reflects on the ephemeral, the fleeting nature of our work.

We painted a mural on the outside of The Laundromat Art Space and exhibited the same mural inside, but on a mobile support, divided into 30 parts. During Miami Art Week these fragments were available for purchase. Each part purchased was a ‘saved’ quadrant of the mural, the fragments not purchased were erased on December 7 for three hours, resulting in a new mural. All of this was broadcast in streaming so that it could be seen in real time.

These processes are very interesting for us because the resulting murals are new to us.

We did the project with Dorcam (Doral Contemporary Art Museum), Ponce + Robles and The Laundromat Art Space, and we were able to produce it thanks to a grant from the Ministry of Culture.

Your work is ephemeral by nature and is conditioned by the passage of time, how do you deal with this and what is your work philosophy?

It is something that is part of our work, since the beginning, when we painted graffiti. There were pieces that we painted at night that when we returned to photograph them one or two days later they were gone. Or else, it is time that conditions the duration.

Therefore we feel that disappearance is something natural and, for us, it is liberating because we do not live with the pressure of something lasting. We have no intention for our actions to remain indefinitely. In fact, as we have mentioned in the case of Miami, we even work with that duration as a conceptual part of the work.

In recent years we have been faced with a new situation, which is the request for restoration of works that have completed their cycle of years. For example in Akron (Ohio), we proposed to create a new piece and the response was that they wanted to keep the one we did years ago. It is strange, but in a way flattering, because it means that the community has taken ownership of the mural and does not want to lose it. That’s why we repainted it again.

How is the work process when you are not the ones who choose the place to intervene, and your objective is to transform society and generate reflections?

We try to make a previous visit to the place to see if the work makes sense or not and to see the context. After that visit, we decide in which area to intervene and we prepare the project ad hoc for that place.

This is not always possible because it depends on the project’s resources, but when we work with cultural or urban planning councils, or with foundations, they understand that this is the best way to start creating a process that makes sense.

In Guadalajara (Mexico), for example, we made a week-long visit to housing units in peripheral communities throughout the city. So, together with the Department of Culture, we evaluated in which of them would make the most sense and why, and we jointly defined the work process. So, once we were back in the studio, we were able to prepare the project specifically for that place and activate the participation of the community months before we started painting.

What is the goal of your work in terms of social transformation, and how has that approach evolved over time?

From the beginning, our goal has been to provoke reflections in the viewer through our works. At some point we have felt a self-imposed pressure to try to transform on a large scale, but over time we have realized that, in the end, what we do are murals, which may or may not inspire people. And, moreover, do it differently depending on the perception of who sees it, but the important thing is that it can act as a vehicle of transmission, an arrow that can go through and connect people. Small actions can generate big changes.

Over time, our perspective has changed and, although we continue to see art as a transformative agent, we are aware of the limited scope.

Is there any project in which you are more closely linked and that extends over time?

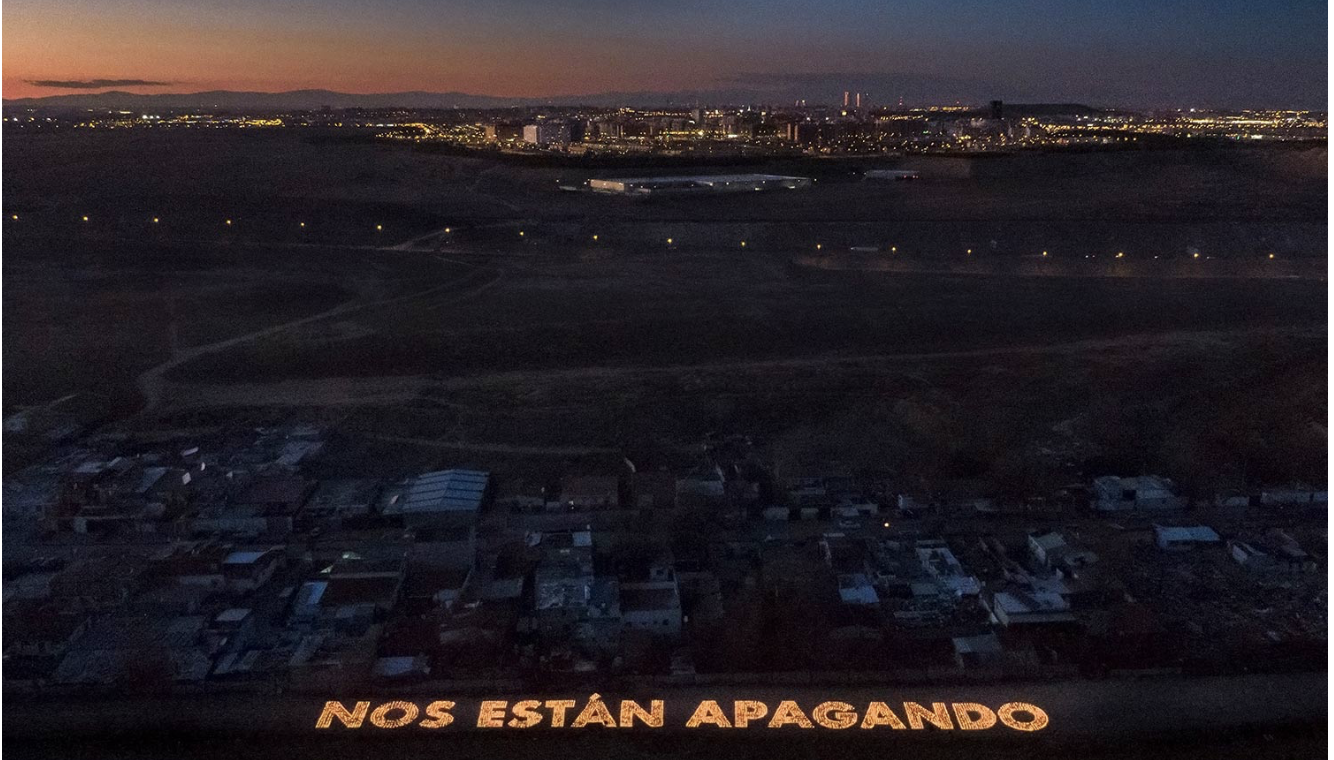

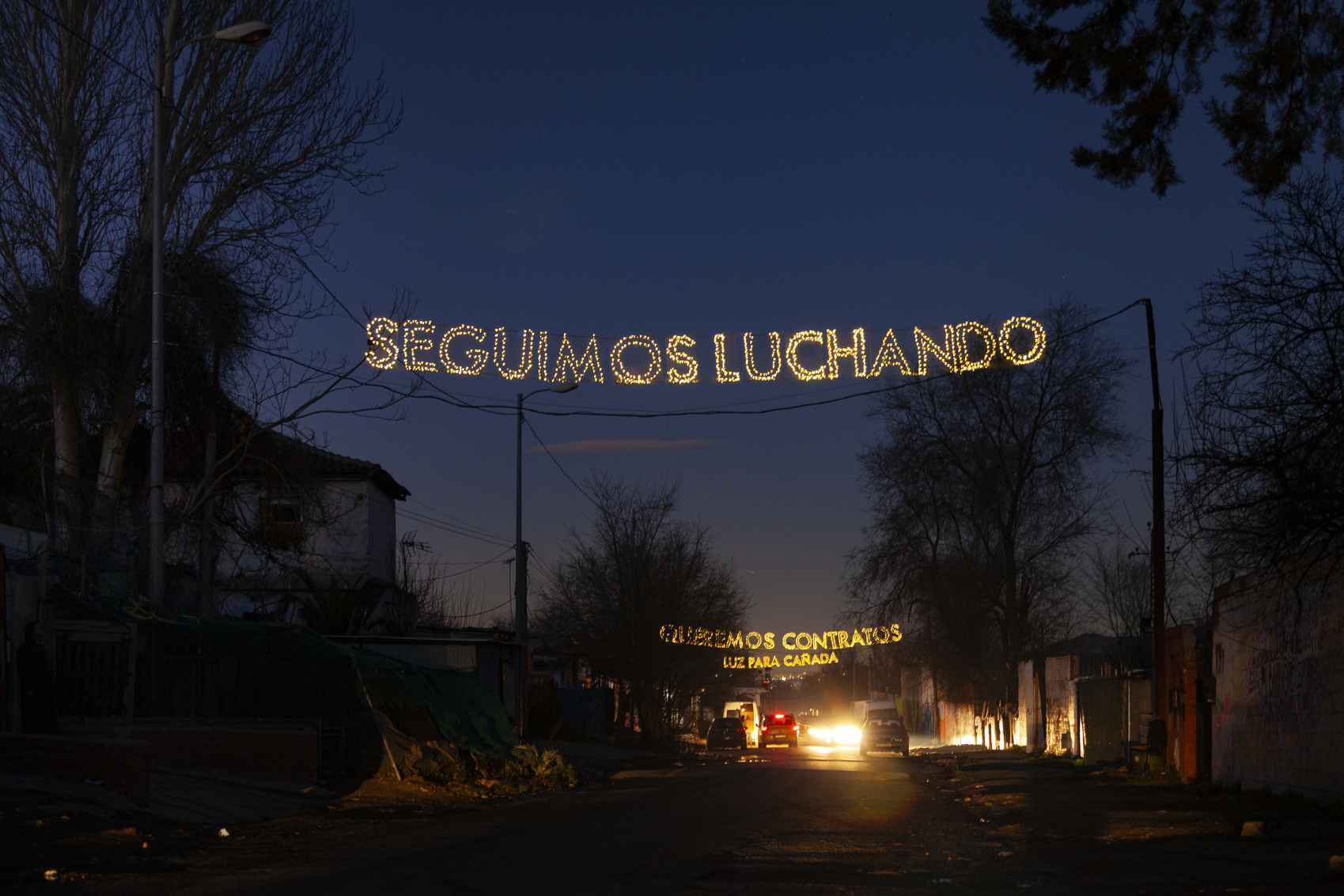

We have a strong link with the Cañada Real, for several years. In 2018, we did a project called El Alma no tiene color. At Christmas 2020, we asked each person affected by the power outage to give us a candle. In total, we collected 4,000 candles and arranged them on the ground forming a 115-meter long phrase, which read ‘WE ARE GETTING POWERED OFF’. This symbolic act took place on the night of January 5 and represented the struggle of 4,000 people for a basic fundamental right. The following year, we made Christmas garlands with solar lights, some of which still remain in the Cañada, with the texts ‘We are still in the dark’, ‘We are still fighting’, ‘We want contracts’ and ‘Light for Cañada’.

Have you ever worked in three dimensions?

Timidly, but it is something that attracts us a lot. We collaborate a lot with Sophie Aguilera, a great friend and wonderful ceramic sculptor. Together we created a series of 40 ceramic pieces in the shape of anatomical hearts that, starting from a common mold, had different vegetation and flowers, making each piece unique. This experience was incredible and although we have tried to bring ceramics to the public space, the grants we have applied for have not allowed us to materialize these projects. We will keep trying.

What other notable project have you done in collaboration with Sophie Aguilera?

She helped us with Leiva’s album entitled Cuando te muerdes el labio. The idea was to design a porcelain box containing the CD and the booklet, vacuum sealed. The choice of the ceramic material somehow defined the soul of the album. The proposal was to put the listener before the decision to break or not to break. But if he wanted to listen to the CD, he had to break the ceramic, symbolizing the process of rupture and personal reconstruction. The piece reflected on grief and the phases of overcoming it, with the idea that the remains of the box would be collected after breaking it. This gave us as many different covers as there were breakages.

What you have done is graphic work, right?

Yes, we sell graphic work through different galleries (Ponce+Robles, Gunter Gallery and Adda Gallery) as well as on our own website. It is a way that people who follow us can support us to continue making projects.

What percentage of your work has been made in Spain and what percentage outside Spain?

Fifty percent. We are based in Madrid, so Spain is where we do a large part of our work, including smaller mural pieces or projects promoted by our foundation. We are currently working on a project with the San Ildefonso school, in Plaza de la Paja in Madrid, to renovate the schoolyard with the students. This week we have been carrying out dynamics with all the school classes and now we are gathering ideas to formulate two projects that will then be voted on by the educational community, before being executed.

Your projects are spread almost all over the continents…

Yes, we are fortunate to be able to know many places and many cultures that enrich us as people and as artists. Almost all of Latin America, the United States, Europe, Africa and some places in Asia such as India, China, the Philippines and Thailand, but we have not yet been to Japan, although we would love to.

It makes sense that our projects are spread across many cities because of the scale they have. If they were concentrated in just one place, we would saturate it.

A dream you would like to see fulfilled?

That we continue doing what we like the most because it would mean that we will continue painting, meeting places and people, and, therefore, being happy.

What projects are you currently working on?

We are working on a very interesting piece on a dam in Germany, in the Westphalia region, which we have been working on for two years and which we will execute in July. We are also working on a project in Paris that we will do in June and another in Querétaro (Mexico), in a juvenile prison. In September, we will be in Santander, intervening in some silos, and we have plans to travel to Manila and Belgrade towards the end of the year.

What is the project that you have done because of its dimensions?

The Aurora building in Heerlen (The Netherlands) was a work process of more than two years that culminated in an 18,000 m2 building that occupied an entire city block. It was a community project that included training for unemployed people, which allowed us to involve the local community and train unemployed people. The mural execution lasted four months. It was long but very rewarding.

Editor: Beatriz Fabián

Beatriz is a journalist specialized in offline and online editorial content about design, architecture, interior design, art, gastronomy and lifestyle.