Interview with Héctor Serrano

We talked to the Valencian creator, National Design Award 2024, who celebrates 25 years of career, two reasons why he is the protagonist of a complete retrospective open at Matadero Madrid until April 20.

Héctor Serrano is a multifaceted designer, able to address a wide variety of disciplines within design, from products and furniture to more conceptual and avant-garde projects. Versatile and committed to social and environmental change, he approaches his projects from an innovative and open perspective, always seeking to explore new possibilities within design.

This is evident in the exhibition Héctor Serrano: El viaje entremedias 25 años conectando, curated by Tachy Mora and promoted by DIMAD as part of Madrid Design Festival, open until April 20 at Matadero Madrid. Among the most outstanding projects, you can see from the design of a toothbrush, to a lamp that floats on water, to educational games for children and adults to a conceptual bus that, still in the process of prototyping, questions and explores the future of mobility and transportation.

In addition, he has worked on installations for music festivals such as Coachella and presented innovative proposals that employ technologies such as augmented reality. Serrano has also been involved in a very special project called Raíces, created after the DANA tragedy and which consisted of collecting roots washed up on the beaches of Valencia, to turn them into pieces of design. This initiative transcends the aesthetic approach, being linked to a charitable cause and awareness of the impact of climate change.

You have been awarded the National Design Award 2024 and you are also celebrating 25 years of career, which is a double reason for the retrospective. What have been the milestones that have marked your career?

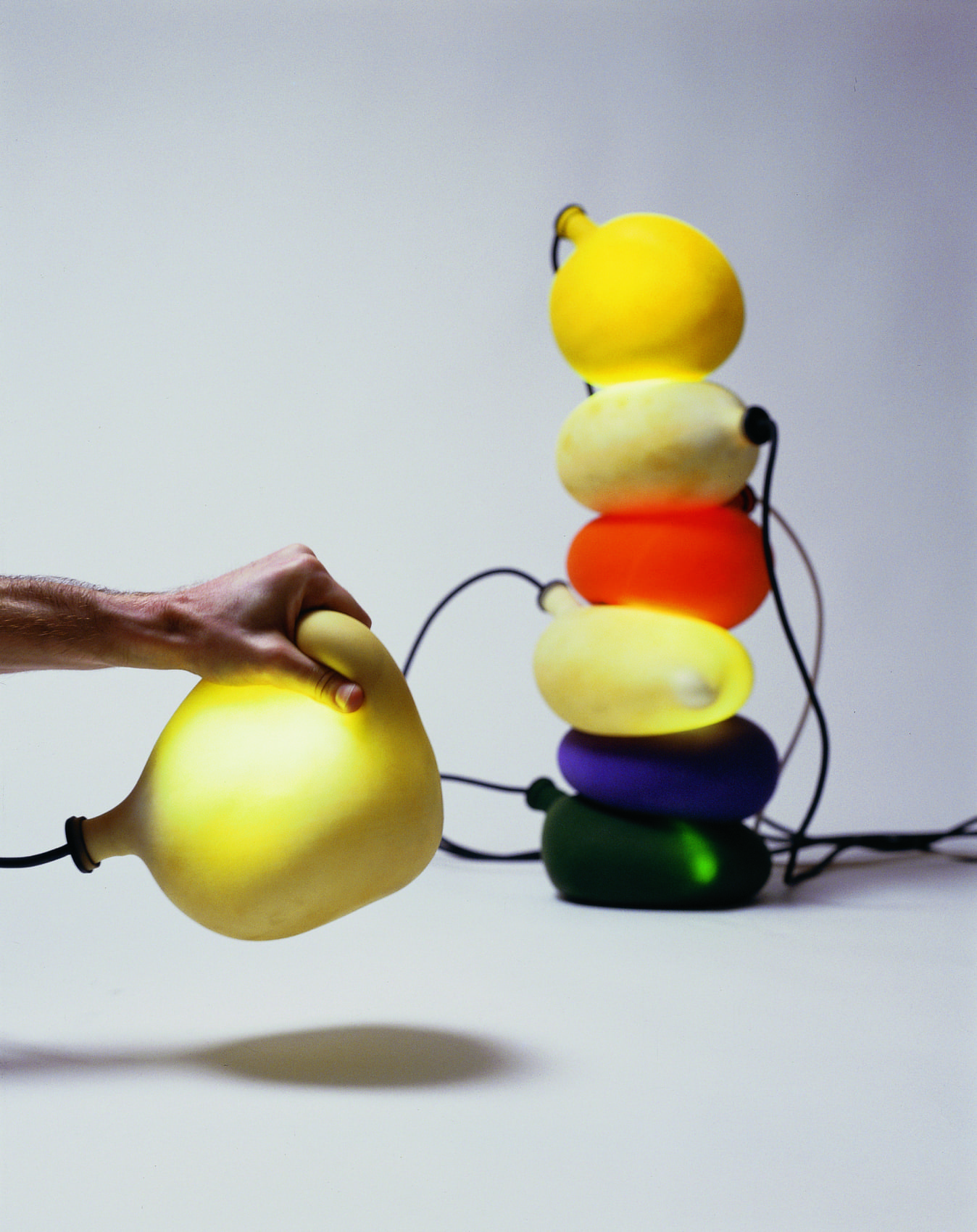

Probably the first one was the Superpatata lamp with which I won the Peugeot Design Award, the first prize right after graduating from the Royal College of Art in London, and one of the biggest and most prestigious competitions at the time. It was on the cover of The Guardian, which allowed me to start making a name for myself. I remember once, walking down the street, a lady said to me, “Your face looks familiar”, and this was one of my first moments of recognition.

In the same last year of studies, I also designed the botijo La Siesta, with Alberto and Raky Martínez, which was one of the first products manufactured by a company, La Mediterránea, now defunct (now published by Diabla of the Gandia Blasco Group). From then on, the career progressed little by little. There was no moment of immediate revelation, but rather it was a constant work, a long-term process. The projects emerged gradually, as in the case of the London bus. Although we didn’t win the award at the time, as it was won by Foster & Partners with Aston Martin, it was key afterwards.

In addition to this, what I value is having maintained long-term relationships with various companies. Although not all the projects have been media or widely celebrated, they are important, long-standing collaborations. For example, I started working with the company A-Emotional Light on the V lamp, a product that is still selling today. I’ve been working with them for more than 20 years, which, while not a milestone, is an example of building long-lasting relationships with customers.

Finally, the most recent is the design for the company Faro, Land, Sea and Air, which has also been relevant in my career. And, of course, the National Design Award 2024.

Why do you recommend visiting the exhibition to the general public?

I think it is an excellent opportunity to understand what a designer does, because we show a great variety of products. You will see that a designer is capable of tackling all kinds of objects and projects, not only products, but also installations, exhibitions, and space design. The exhibition is a range of many different typologies and processes.

In addition, the way the exhibition is organized is key. Not only the final result is shown, but also the process behind each project. We want visitors to understand the thinking and decisions that are made from the beginning to the end of the design process. It’s like a journey, a tour through the entire creative process.

What has the awarding of the National Design Award meant to you?

It represents an important step and is, without a doubt, one of the greatest national recognitions you can receive. It’s like a seal that validates your trajectory and your work, backing up your credibility, especially when you talk to clients, future collaborators or even other companies.

Your designs have that thing you call ‘unexpected ingredient’, explain to us what it is and why it is always so present?

This concept is something that is actually born in our studio. We don’t have a formal style, we don’t follow a specific aesthetic line, nor do we repeat patterns in terms of shapes or curves. However, when you look back and analyze the projects, you do notice that there is a particular way of approaching the projects, a way of understanding them and a process that, although it may vary in each one, is repeated in some way over time.

These formulas we use in the studio are based on ‘familiarity’. We like to play with the collective memory we have of objects and how we perceive them. That collective imaginary is part of what we try to explore and bring to design, creating something that, despite being novel, has an emotional connection and a certain familiarity with the public.

I like the idea of taking something very familiar and transforming it into something new. It’s like when you meet a person and, at first, you feel a connection, an attunement. And then, over time, that person surprises you with something new that you didn’t expect. That’s the ‘unexpected ingredient’. It’s a way to innovate, to give a twist to the familiar and turn it into something surprising and fresh.

Does that ingredient vary from project to project?

Yes, it depends on the project. In some cases, it may be the material used, in others the context or even the inspiration that shapes the idea. Each project has its own characteristic, but there is a continuous line. For example, in the case of the Superpatata, which is soft and has an unexpected shape, or La Siesta, which does not have the traditional shape of a botijo, but is more like a plastic bottle. They are projects that propose something different from what is expected, and in that sense, I seek to generate a surprise or a reaction in the person who observes or uses them.

Do you see it as a game or a challenge for the interlocutor?

In some projects, yes, there is a much more evident playful aspect, but it is not always intentional. Sometimes the inspiration comes from the idea of creating something playful, and that is reflected in the object. But in other projects, the playful component is not so visible or prominent. I think it depends a lot on the idea and the motivation behind each design.

Is there a characteristic formal language in your work?

I don’t think there is a formal language that is so clearly defined and easy to identify. Rather, what predominates is the idea behind the object, rather than its form or aesthetics. It is an idea that manifests itself in the product, but not necessarily in a visual style or in a very marked aesthetic. That is something that is more behind, in the concept of the object, than in the form itself.

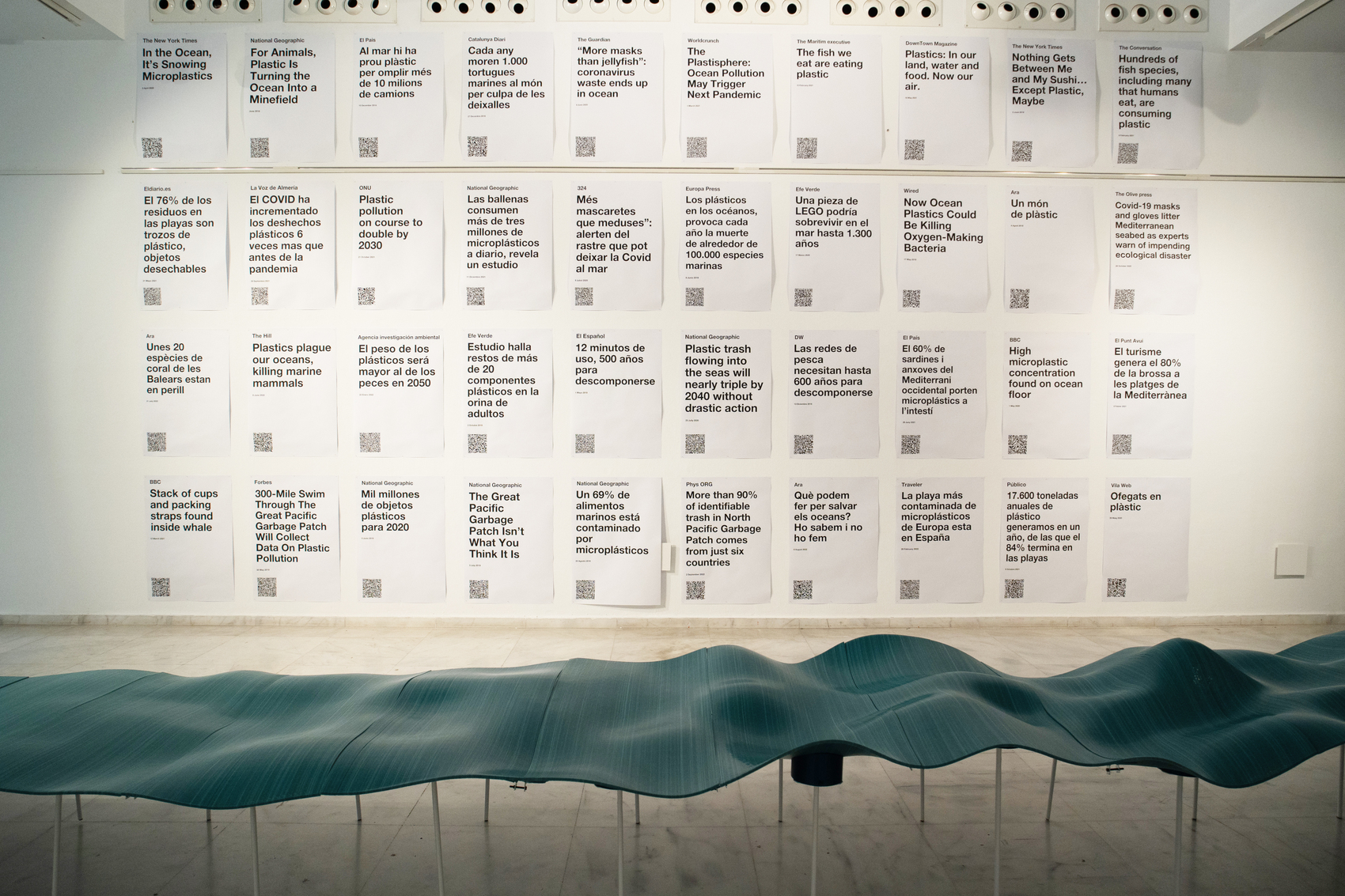

Sensitivity and commitment to the environment are common points in many of your designs, how is this reflected in your most recent work?

A clear and current example of this commitment is the design of lamps for Faro Barcelona, under the collection Tierra, Mar y Aire. These lamps are made from 100% recycled and recyclable bioplastics and plastics, fishing nets and a material derived from cellulose, and are produced using 3D printing technology. The use of these materials not only takes into account sustainability, but also the possibility of producing them more locally, reducing the carbon footprint.

3D technology allows us to produce more efficiently and locally. Unlike traditional factories, which require large spaces and molds to produce on a large scale, with 3D printing we can manufacture on demand, without the need to store large amounts of inventory. In addition, the machinery we use, such as robotic arms, is much more compact and adaptable to different production environments. This makes it easier for us to produce closer to the consumer, right now they are being manufactured in Madrid, Barcelona and we are even thinking of making them in other cities around the world, without having to rely on mass transportation.

How does this affect the traditional production model?

The traditional mass production model seeks to lower costs through large-scale production, making thousands of units with molds, which reduces the cost per unit. However, with 3D printing, production is slower, as you produce one unit at a time, but you don’t have the costs associated with molds. It’s like a mix between craftsmanship and digital technology. This makes it possible to create custom-made products, tailored to the customer, which gives them a unique and personalized character. The key is that this form of printing has been done to create prototypes, but, in this case, you get the final product.

Is this technology easy to find on the market?

A few years ago, this technology wasn’t widely available, but today it’s become more common. The robotic arms we use are the same ones used in the automotive industry, and we’ve adapted them with specialized injectors and proprietary software to enable 3D printing. Today, this technology is more accessible and is developing rapidly to make it more standard and accessible. Furthermore, the materials we print with, such as recycled plastics or fishing nets, are increasingly available.

What do the materials you use in the designs for Land, Sea, and Air represent?

Each of these lamps has a message related to sustainability. The Land lamps are made from recyclable plastics, which highlights the importance of considering recycling and the responsible use of resources. Sea is related to fishing nets, which represent one of the largest sources of ocean pollution, with 360% of the plastic found in the sea coming from these nets. And Aire uses recycled plastics from water bottles, highlighting the need to recycle more, as only 10% of the world’s plastic is recycled properly.

Its design references nature, such as bubbles, hedgehogs, and honeycombs, resulting in organic shapes that evoke the relationship between humans, nature, and technology. The use of colors such as honey and earthy tones also reinforces this connection with the earth.

Your work encompasses a wide variety of products: toothbrushes, intelligence-building toys, lamps, spoons, kitchen utensils, and even a bus. Why did you choose not to limit yourself to just one area?

I’m very drawn to the idea of learning and taking on the challenge of new projects. I don’t want to be trapped doing the same thing over and over again, with the same types of products. The variety in my projects allows me to explore different approaches and stay creative. At first, I was somewhat pigeonholed as a lamp designer, which wasn’t what I wanted. Although I started with lamps, like the Waterproof lamp for Metalarte, which opened many doors for me, I’ve always wanted to diversify. Innovation is key, and I’ve tried not to limit myself to just one discipline.

Don’t you feel limited by being associated with only one type of product, like lamps?

Exactly. Although my first major success was with lamps, the idea of being labeled only as a lamp designer didn’t appeal to me. It’s important to have a broad vision and not fall into the routine of always doing the same thing. Designers, in my opinion, have the ability to learn from many disciplines and processes. I may not be an expert in a single field, but my experience gives me a comprehensive understanding of processes and allows me to extrapolate ideas from one area to another. This can lead to unexpected solutions in a project, which I believe is part of creativity.

Does each project have its own technical challenges and require specific knowledge?

Yes, each project is unique and brings its own difficulties. For example, with the Furniture collection, the process was very long due to the complexity and investment required to create large pieces. The challenge is that, while creativity and a general vision are essential, it is also crucial to have specialists to help bring those ideas to life. In this case, it was necessary to work closely with the Furniture technical office to ensure the pieces could be properly industrialized. Projects like this require very specific technical knowledge of industrial processes.

So, do you need the collaboration of specialists to carry out certain projects?

Yes, definitely. Creativity and the initial concept are only part of the process. When it comes to bringing an idea to production, it’s essential to have experts in each area. This ensures that what we proposed in the design can be effectively realized, without losing the essence of the project. Each piece, depending on its complexity, requires a specialized approach to ensure technical and quality standards are met.

The Matadero exhibition concludes with a very special micro-exhibition called Roots. What can you tell us about this project?

Roots is a collection of 85 vases made from roots collected from the beaches of Valencia after the devastating passage of Hurricane DANA. These roots, which initially looked like branches, became the materials we work with. We collected them from the beaches, from the south of Valencia to 40 km further afield, and what struck me most was seeing the power of the water and how all this natural material accumulated on the shores. The exhibition displays each vase with the name of the affected towns and districts of Valencia.

Each vase is unique, as each root has its own language and shape, and this also has a charitable component, as sales from this collection go to fund family farming projects in areas affected by the storms, such as the Sot de Chera region. Although the amounts raised are not huge, the main objective is to highlight the issue and raise awareness.

What happened in Valencia was devastating, and there are still many people living in precarious conditions, such as in Paiporta, where houses near the ravine are collapsing. Many people still lack access to basic services, such as education, due to the damage. Furthermore, this project also has a global vision: highlighting climate change and how our actions are destroying the planet. It’s not just a matter of protecting the environment; it’s about saving ourselves.

On the impact of climate change and solutions

The problem is much more complex than it seems. There is no easy solution, but one of the most powerful forces we have is as consumers. If consumers demand sustainable products, companies have to adapt. In fact, they are already doing so, not because of goodwill on everyone’s part, but because the market is demanding it. Many companies that previously sold products with disposable plastics have had to change.

We all need to push, as a society, for more effective policies and for companies to adapt to a more sustainable model. Ultimately, consumers have a lot of power, and that power can generate significant change, both in terms of policies and business practices.

How do you see the future of design?

The future of design, especially in light of climate change, is an exciting field full of potential. It’s a powerful tool, but it’s not the only solution. It’s part of a collective effort involving diverse industries and disciplines. It can’t save the world on its own, but it can contribute to a positive impact, especially if applied ethically and responsibly.

Design has a promising future because, ultimately, it’s a matter of judgment. Design isn’t just about creating products or spaces; it’s about constant decision-making. While artificial intelligence can help with automation and quick solutions, the true magic of design lies in human judgment. The ability to decide what is right, appropriate, and what makes sense from an ethical, social, and environmental perspective is something technology cannot replace.

Designers play a fundamental role not only in the field of product or spatial design, but also in the creation of broader services, experiences, and solutions. Decision-making based on a conscious and responsible approach is key, and this is where the designer has much to offer. So, although the future of design will face challenges such as climate change, sustainability, and rapid technological evolution, it remains a discipline with a bright future if it focuses on positive impact and responsible innovation.

You also do educational work. What advice do you give to future designers?

I don’t think there’s a magic formula, but the most important thing is to love what you do. It’s essential to find what truly motivates and excites you. In my case, at first, I tried to explore different areas and try out many things. I think it’s a good strategy for knowing where you want to direct your career. Once you have a clearer idea of what interests you, you can delve deeper into that path and begin to specialize.

Tell us about Borealis, another of your areas of work.

We first did an installation for Roca, which opened the door to music festivals. We participated in the Coachella festival and continue to do installations because they are very engaging projects and allow us to explore new forms of art and experiences, and do so with a different approach.

One of our latest projects, for example, is the Christmas tree in Barcelona, with augmented reality. The interesting thing is that, although the physical spheres were on the tree, with your phone, what you saw was the entire plaza filled with these virtual spheres, creating a visual impact without affecting the space as much.

What stage is the bus at? Are you making the prototype?

We’re working in the initial stages of design and prototyping. The process of designing a bus is complicated because it affects the entire production process in the industry. We’re also currently working on another bus, but this one will be commercial, unlike the previous concept, which is a more experimental idea.

Horizonte will be autonomous, driverless, and more focused on technology and sustainability. It’s a similar concept to what car manufacturers use at auto shows, when they present a concept car that isn’t intended to hit the road, but serves to show where innovation and the future are headed. In this case, the bus isn’t intended to be mass-produced, but rather to question the future of transportation.

A dream you’d like to see fulfilled?

Although it doesn’t have much to do with work, it would be to be able to spend more time with my family. I really like surfing and I’d like to enjoy those moments with my children, who also enjoy it. Also, traveling more with my wife, although she’s not that interested in surfing, but ultimately, the important thing is spending quality time with loved ones. Time is the most valuable thing in life, so I’ll try to make the most of it. Lately, I don’t know, it seems a little more difficult, but my goal is to continue finding time for what really matters.

Written by: Beatriz Fabián

Beatriz is a journalist specializing in offline and online editorial content on design, architecture, interior design, art, gastronomy, and lifestyle.