Interview with Rosa Escandell, co-founder of ADCAM project

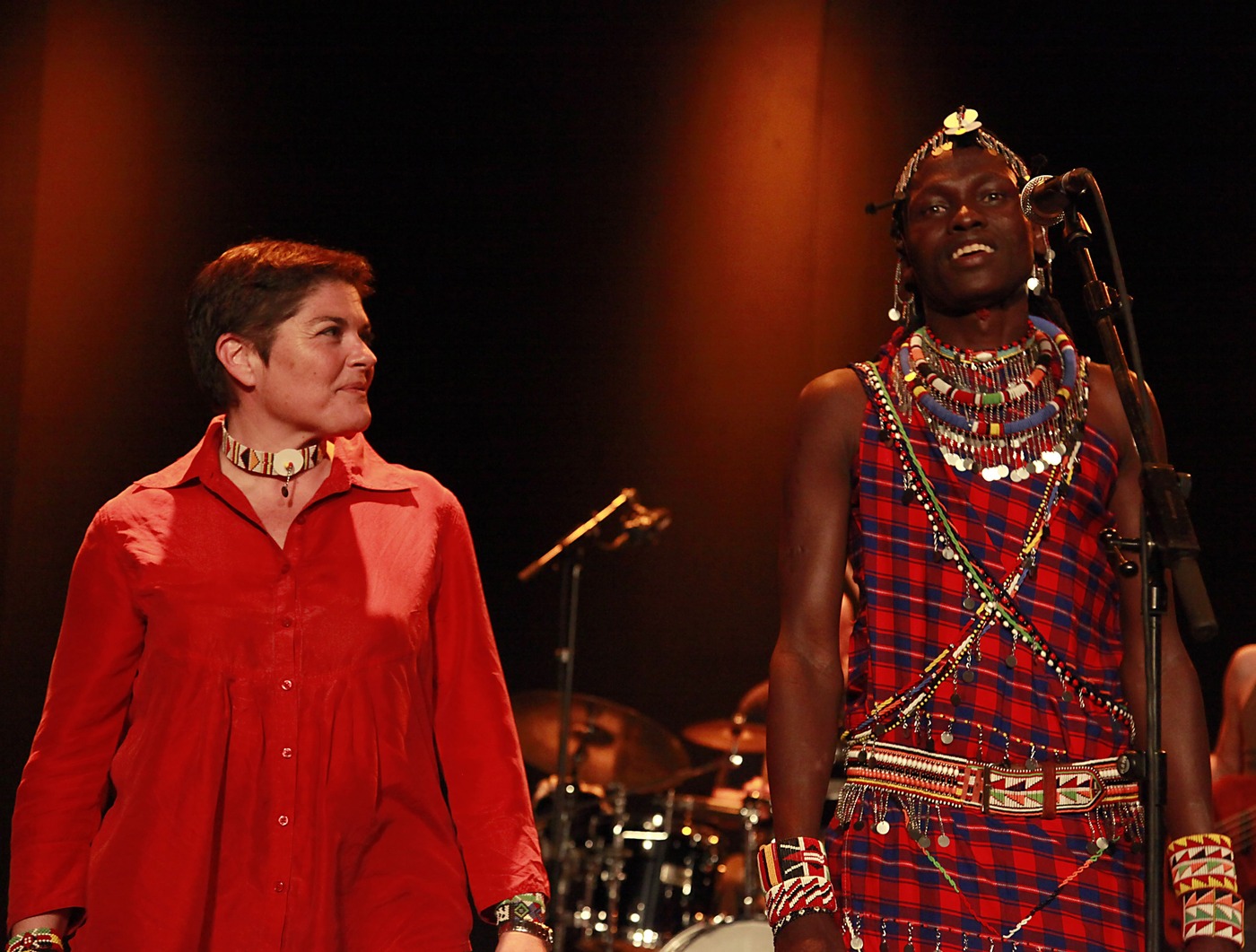

We interviewed Rosa Escandell, co-founder along with William Kikanae Ole Pere of this unique project of great purpose. It has been twenty years since their paths crossed and they created ADCAM, a project dedicated to preserving the Maasai culture in Kenya.

How and why did ADCAM ONG arise? What is the mission you pursue and what needs did you see in the community to start this project?

ADCAM arises from a personal concern of mine to give opportunity to people in the way that I have seen throughout my career that is the most effective, which is through employment and training. Since I was a child, I have been fortunate to be in a family where I have been able to be who I wanted to be, with the freedom to decide at any time what I want to do and where I want to be. I have always thought that everyone should have those options. Unfortunately, it depends on where you are born, because you already have a part of your path and your trajectory marked or fixed, but I believe that through education and employment you can change lives and generate opportunities. And then, everyone can decide. ADCAM is a development, alternative trade and microcredit association, and those words encompass entrepreneurship, work and opportunity. The community doesn’t just start in Kenya. ADCAM starts globally with work in Bangladesh, with a project in Brazil, but logically the one that has been given the most dedication is the one in Kenya.

Rosa, your trajectory in the financial world managing microcredits for projects exposed you to many initiatives with social impact. What attracted you most to William’s project and how did you decide to take that big step to become fully involved?

What struck me most about William’s project and deciding to support him was first his determination. I met William in Kenya through the Spanish embassy in Nairobi. I was invited by the government and by Wangari Maathai, who is a Kenyan Nobel laureate, to develop microcredit in the country. At the last moment, when the embassy told me “there is a person who has been coming to Nairobi for ten years asking for help and he is a Maasai”, where I was already aware of the UN declaration of a tribe in danger of disappearing and I knew a little about their way of life, I thought that there was a determination, that he had to be a special person because ten years is a long time. Ten years from the savannah to the city was already decisive. Later when I interviewed him and I was aware of his motivation, of education as part of development but he told me that he had been chosen by a scholarship from Michael Jordan to go to the United States for eight years and that he gave up that dream of his life to learn. William was a gifted child in the savannah, extremely poor. And that he walked 25 km to go to school is one step, that he didn’t have shoes is another, that he didn’t have pencils is another, but that he gave up going to study in the United States on a scholarship to fulfill his dream, that seemed to me to be an incredible determination. I already saw that he was a special person but to be honest, what impacted me the most and what made me decide to do this project was when he began to tell me, how through his mother, who had been the one who had sold a goat for him to study, he saw the need to empower women. That thanks to his mother and that if all women like his mother had money, his community would change. Since he was a child, he was already making a change to empower women and that was when it was clear to me that finding an African man, in a tribe twenty-two years ago, who was clear and who was making that change from within to empower women, loving men, loving warriors, because now we talk a lot about integration, that this is a matter of everyone, but twenty-two years ago it was not said that part of this process is that men are involved. That fascinated me and I was also aware that it was one of the dreams of my life, to empower women in the world and give them those opportunities. I was also aware that I from the western side, as a white woman could not do it, so also through him I fulfilled my dream.

The beginnings are usually the most difficult. Could you share how was the experience of launching ADCAM in its first years and what were the main challenges you faced?

I agree on the difficulty of the beginning. Startups usually begin with an idea and until that idea materializes it is very difficult for someone to believe in you. In my case I already had an important personal background and trajectory, but it is still complicated. Trust begins when the project is already underway, when something already exists. And that also has repercussions on the economic side. Nobody finances a project from scratch and that’s where I had to put all my economic resources from my many years of experience to start. I would say that was the first part of the difficulty of the first years of ADCAM and the challenges were many, because William tells precisely how he, for ten years, received tourists in his “manyata” who promised him many things that were not fulfilled. It is true that you get there and it is so fascinating the community, the nature, the environment, that you feel so happy with that intention to help, but then you go back to your day and you forget about it. So he told me, “if you want to work with the women they have to trust you and that means coming and getting to know us from the inside”, and well, for the first seven years there was nothing, there was no project, but I went to live in the “manyata” for long periods of time, without any resources, in a one-body tent, and the first challenge was them. That they trusted me. As an anecdote I tell that it took almost a year to make me a breakfast, and I lived with them, I was with them.

Later, another important challenge was the “rangers”. The community where we were located was a leopard zone. We were beginning to work with women, the community began to grow, and they considered that this could be a danger, so the “rangers” expelled us from there, so as not to make noise, not to grow, not to bother the leopard. On the other hand, the community itself and the warriors did not understand that the process of women’s empowerment was a benefit for the whole community. Also nature itself, the animals, living in a hostile environment, diseases, drinking water from the river… it is true that there were many challenges, but little by little and with time we faced them. I think that in the end there was also a very important part that I believe that William and I were born to fulfill a mission and in that mission we had many angels that protected us, that were with us and that kept us going because those first years were very complicated and very difficult. We also started with the women’s project, so that they could learn to work the leather, to take care of the leather and to make a design different from what they knew, so there were many challenges but also very nice ones. I remember it with great affection.

Throughout these years, you have made significant achievements. Could you highlight the most important milestones in ADCAM’s history and what they have meant for the Masai Mara community?

The most important milestones are to be here, after twenty-two years. We have done a project with a head, with an entrepreneurial vision, which is what has kept us going. Now there is a little more talk about social entrepreneurship, but I have always thought that associations and NGOs are businesses and that they should be managed from there and not be 100% dependent on the administration. I think that in this sense ADCAM has done well, through the creation of this “lodge” that finances the project and also through the sale of handicrafts. The project starts with women. When I met Bibi Russell in Bangladesh, ambassador of UNESCO for its fashion for development program, which consisted of giving them a design guideline to later commercialize; that is, to buy the handicrafts of the world not because you feel sorry for them, but because they are beautiful and this is something I deeply admire in Bibi and I had lived in many Latin American countries. You cannot buy out of pity, handicrafts are a luxury and with that design guideline you can market them. That part has been very important. We have created a cooperative of 1,400 people, but this has also allowed women to have money for the first time, to buy cows for the first time. What a beautiful moment and that we also taught them to create their own businesses through the Masáis collections of Pikolinos, which we did for 6 years and which had a very important economic impact on the community. We taught them how to create businesses with that money, because in the end fashion is fashion and always has a beginning and an end. In this sense, we wanted them to learn how to manage. I think this is very important and it is also true that apart from the economy, the school’s education, there has also been a very important part, which is to get to know each other. That cultural part of north-south of what I represent as Spanish or as European and what they are, to make us know both parts or even between the masai themselves. I remember when we made the formation of the sandal collections, in the Masai Mara we brought Tanzanian women who had never seen each other. Sister Maasai who had never been together and then we would do the training together. Some told the others how they made the houses and exchanged opinions and I think that this knowledge of the culture of both sides, of how we are, is also very nice and important.

Twenty years after starting this adventure, have the dreams that each of you had when you started this project been fulfilled? How have those aspirations evolved over time?

I think so. William’s dream of bringing education and empowerment to women and my dream of supporting African women has unquestionably been fulfilled. In fact, the fact that the project is here, that it continues, is a satisfaction. The evolution of the project and how we see what is going to happen, obviously we continue dreaming and now we are in that second phase of creating a Professional Tourism Training, which in the end is the only economic resource that exists in the Masai Mara so that this community settles in their land, they do not have to flee to the city, they have jobs and opportunities, because we all know how important safaris are in the world and their economic impact they have. They are in the Masai Land and they are not affected, they are not employed. That is what we want and above all William’s dream that the warriors continue to have a position in the Mara. They can no longer graze as they used to, take care of the cattle… the lands have been limited by the reserves and to give them that option of employment as guides or as any other employment in a hotel or in a lodge we think it is very important. We are satisfied and now both William and I think that this project does not have to stop, that it is for generations and generations, that it belongs to the community and we feel that the community feels that way, so I hope that we can fulfill this second phase. So far we have fulfilled our dreams, yes, and we continue dreaming.

How has ADCAM transformed life in the Masai Mara community? Could you describe the most notable differences in the quality of life before and after the NGO’s intervention?

The change in the community has been substantial and very important. First, the change in the vision of women; that is, that women can have money, that they can have a job without neglecting their chores at home and their role as mothers, which is so important for the Maasai community. To see that empowering or training women does not mean that men are annulled and it does not mean that they are going to be above them. From the moment that they have seen that they continue to take care of their day to day life, their home, their children, their work, but they can also generate income and contribute. To see how the warriors, who at the beginning wanted us out, now help them with water, wood or taking care of the children so that they can work, seems to me an incredible transformation in a community with a culture like the Maasai. Also education, that key to development. For example, this year we have had a young intern, Benson, whose mother was a user of the women’s project. She worked with us making handicrafts and thanks to that money she has been able to pay for her son Benson’s studies, who has gone to tourism school. It has been very nice to see how this second generation is changing the community through education and also former students from the ADCAM school have come to tell me, “look Rosa, thank you, this is my life, this is my work, here I am…” it is very important to see how the Masái community still wants to stay in Masái Land, they are not so anxious to leave and not come back. I think this is an important point and I think this also has to do with the rootedness and how proud a Maasai is of being Maasai and of the land where they live, which they also feel as the most beautiful in the world. William also transmits this very well to his community. So we are talking about generating economy, we are talking about education, we are talking about cultural exchange. And I think this is a quite remarkable change and thanks to ADCAM all these things have been possible.

How does the Maasai community see your project, as well as clients and institutions that have supported the ONG?

Having created this project from that base that was those beginnings where I go to live with them and where I create a relationship of trust after many years, makes the community see the project with respect, with affection, as theirs and above all with trust. The community knows that ADCAM is there. ADCAM transmits and tells them the good, the bad, the regular, what is happening and what is not happening, what is possible and what is not possible and what the situation is at all times. The project is theirs and that is how the community sees it. From there, any client, institution, friend, client of the Camp that comes from ADCAM is family. For them we are a family, everything that comes from ADCAM is family and they know that everyone who comes from here supports them so that their dream continues and is possible. From the volunteers, the training, the clients of the lodge… they know that they are there to accompany them without distrust and it is an extension of the NGO. From this point of view, I am very satisfied.

Where does the most significant support for ADCAM come from, and how have you managed to maintain the project, what additional resources or support would be necessary to ensure the continuity and expansion of the project?

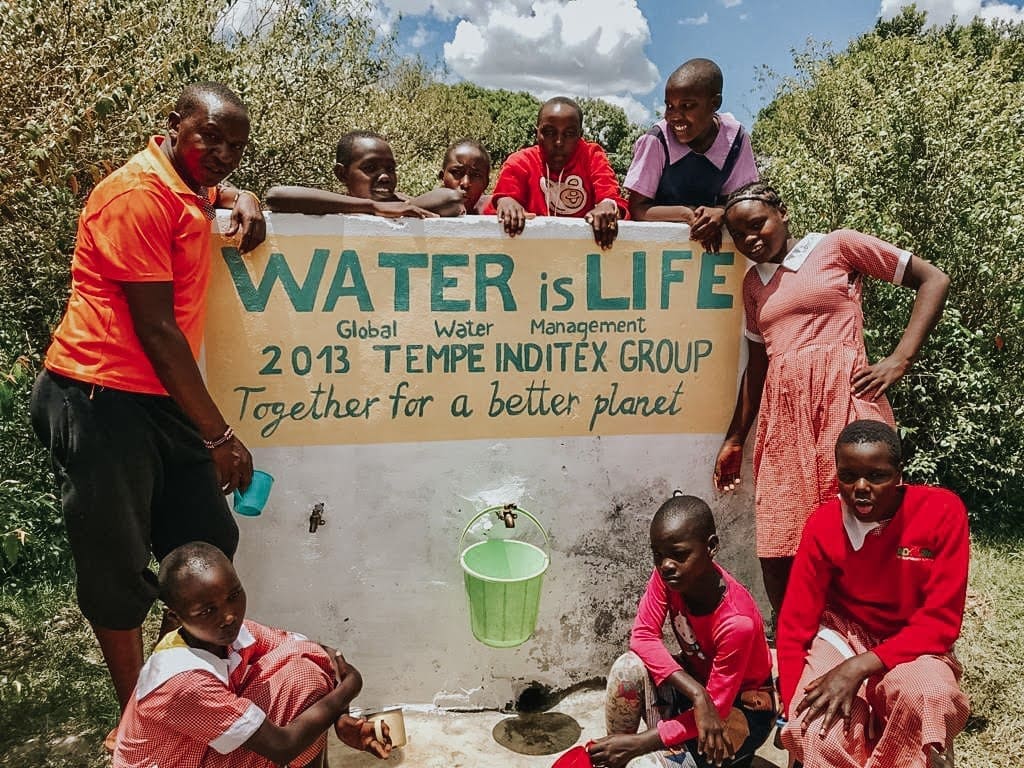

As I said, initially it started with my funds and from there there there is a company that is a friend, collaborator and financier from minute zero, always, which is Tempe of the Inditex group. Thanks to Tempe and the Inditex group we have had the solar panels that have changed the life of the school and have allowed us to have the lodge that ADCAM now finances and the well. We found water at a depth of more than 140 m financed by them and this has reduced infant mortality by more than 40%, supplying water for the whole community; that is, from drinking water from the ponds to drinking clean water. Apart from that, from Spain we have had the support of the Provincial Council of Alicante, the Alicante City Council for a couple of years and private foundations and institutions and a system of sponsorship of children, which in the end is a sponsorship of the school, but that allows us to have a monthly forecast of our income to be able to plan what we spend it on at the school. In the end, this is also part of the ADCAM family that accompanies us and is an important part of the project and that later they come to visit us. In recent years, what has brought us the most income is the lodge. The idea of creating this camp hotel for safaris, being William a National Geographic guide who knows his land like no one else, accompanying Jonathan Scott on safaris… we thought that making this lodge and also turning it into a project for the reinsertion of warriors into the labor market, training them in the different areas of the hotel business so that they can later find a job in other hotels and not remain as porters, I think it is important. The lodge is financing almost 70% of the project at the moment.

What future projects are in development and how do they align with ADCAM’s overall mission?

We have just materialized the first one, which is the High School. The Senior School has now been approved up to level 9, which means that we have a kindergarten, the primary school and the high school. It is a prelude to the University and after much reflection we realized that a Maasai has very few economic options to go to Nairobi or Narok to the University and that also makes them lose their culture and leave their environment. Hence the idea of creating a professional training in tourism. The idea is to train the trainers so that they can then transmit it to the whole Maasai community. To take the tops of our world and share with them the benefits that we have had through our education, which in many occasions is superior to theirs, and to transmit it so that later they themselves can train the whole community and generate employment. Women play a very important role in this professional training. We are working a lot on computer training and this can allow Masai women to have a job in a hotel reception and at the same time be mothers, which is important for them. In this way they can have a more advantageous position than cleaning or being a kitchen maid. This idea of responsible tourism does not come only from ADCAM’s vision with William, it is the product of all the years we have been working with the community, analyzing their needs and also knowing that they agree with this decision. I think that the whole pillar of ADCAM from the beginning has been to share with the community and see their needs, not ours.

In the current context, what are the main challenges facing ADCAM and what are your goals for the coming years?

One of the challenges we are facing is what is going to happen with the Maasai culture, how they are going to maintain and evolve this balance between what they are and what they are learning and introducing from education, from globality. In the old days it took eight years to become a warrior, now it takes a few months. The concept of warrior almost disappears, but it is not only the culture but also what is going to happen with the Masai Land, with the land. The conservation areas have grown at this time, there are 11 and a certain war between conservation areas and animals, for the economic benefits that this produces. The lands are starting to be fenced. In the Maasai territory the government does not allow the purchase but the leases are now limited to 25 years but before they could reach up to 50 years, with which the Maasai themselves lost the right to their own land. Prices are going up. I think the challenge is not only in the Maasai culture but in what the environment is going to make the Maasai culture to be. Difficult to answer, I don’t know. What we do, of course, is to organize as a priority, from the educational point of view, some extracurricular activities at school so that the children can maintain their culture and their way of life. I think that can help a lot for the future.

For those of us who are interested in supporting from here, what is the most effective way to collaborate with ADCAM and contribute to the welfare of the Masai Mara community?

Well, from here there are many ways to collaborate with us. One of them is to sponsor a child, to help the school through this sponsor. Another very important one is the issue of women’s handicrafts. I invite anyone to make a market, an exhibition, a purchase of handicrafts, a marketing through distribution companies … on the other hand we have a second project that we call Sawamara, which is a land where we want to create this professional training, but also to give sustainability to this project we had thought of focusing on a lodge that we have already built for digital nomads, for travelers. The lodge is located in an area that despite being in the savannah is not within the reserve, so the reservation fees of the 11 reserves of the Masai Mara today, are at 100 € per person per day, which makes it more affordable to stay longer stays, or come with family, and from there to know Kenya, or telework. This is a project that excites us. We have the land, that nowadays it is very difficult to have options to make a lodge, since in most reserves it is no longer possible due to overcrowding.

We have the experience, the services, the land, including the National Reserve, which is where the wildebeest crossing takes place in July, August and September, and what we would love is to find someone, from the tourism side, from the hotel side, who wants to get into the Masai Mara and support us in the management of our lodge, Sawamara, the National Reserve, all that tourism side and that allows us to dedicate ourselves exclusively to the social side. This would be the challenge we face now and the most important support we could have.

From a personal perspective, I do want to convey that this project has taught me a lot. What I have learned from the Masai community is presence, living each present moment with acceptance. Learning that not everything is in our hands. Maybe because they are so close to nature, they have it naturally since they are born. The beauty of this country is incredible and in these 22 years I have lived magical moments, sharing with wonderful people, clients who are now friends and family. I have felt that all of this makes sense and that has been my driving force to keep going.

More information about ADCAM

Writing: Silvia Hengstenberg.

Photographs: ADCAM.

ADCAM will be presented in Madrid on January 21, 2025. See related article.