‘Art has taught me how to see’. Luis Bassat

Luis Bassat speaks candidly with Silvia Hengstenberg about what we still lack: more museums for living artists, greater involvement from institutions, more beauty in our cities, more peace in the world... and about what endures when everything else changes.

At his 83 years old, he still thinks with the energy of someone just starting out. He has devoted his life to seeing things differently. A pioneering advertiser, passionate art collector, and advocate for dialogue and beauty as drivers of change, Luis Bassat reflects in this conversation on his life through the lenses of art, advertising, family, and social commitment. From founding his gallery in the 1970s to his current perspective on artificial intelligence, Bassat shares candid stories, lessons learned, and his vision of what it means to create, communicate, and leave a legacy. Together with his lifelong partner Carmen Orellana, they have built a collection that stands as a declaration of values — and his words, a generational manifesto.

A story that left a mark on you

I wanted to be independent, not rely on my parents. I wanted to smoke and buy a Vespa. But, of course, my father didn’t want me to smoke or have a motorcycle. So I decided to find a job and start earning my own living.

At 16, I found the job I was looking for at Correos, the Spanish postal service. They were hiring university students to work for a full month, from December 6 to January 6. I applied, even though I wasn’t yet a university student, thinking that if they asked me to organize routes or handle logistics, I’d know how to do it. And they accepted me.

On the first day, we were gathered in a basement at the main post office in Barcelona, with small windows opening to the street. A man explained to the 200 young people there that mailbags would come down through those windows and had to be carried to another room. I remember many people left as soon as they heard that. I stayed. And I stuck it out.

There were fewer of us every day. On December 31, I went out with two friends to celebrate New Year’s Eve. I slept for only two hours, woke up at five, and went to work. On January 1, I was the only one there. And I stayed until the end. I couldn’t quit. It was a matter of self-respect.

That experience shaped me forever. Since then, no job has felt hard. I’ve spent countless nights working on ad campaigns without sleep, and the next day I kept going. I endured. Because after carrying sacks for eight hours a day for a whole month, everything else seemed manageable.

I clearly remember another story. A client told me I had to be in Barcelona on a Wednesday morning to present a campaign to Schweppes Europe. I told him that Tuesday afternoon I had to be in New York to present the European campaign for American Express to the global CEO, and that the meeting couldn’t be moved. The president of Schweppes insisted he had to see me on Wednesday morning, and since the American Express meeting also couldn’t be changed, the company itself arranged the trip for me. I flew out of Barcelona Tuesday morning. When I arrived in New York, I took a helicopter to 34th Street in Manhattan, where an Ogilvy car picked me up and took me to the office. There, I showered, changed, and the same car took me to American Express. I presented the campaign, which was enthusiastically approved, and then an executive from the company took me to their helipad. Another helicopter took me back to the airport, where a car was waiting to drive me straight to the steps of the same plane I’d flown in on that morning. A different American Express executive handed me my passport—he must have cleared it through security himself. I sat in the same 1A seat. I was exhausted and fell asleep immediately. When I got to Barcelona, I went home to shower and then got a call from my assistant who said, word for word: “Today you’ll kill someone. The president of Schweppes just canceled the meeting.” I called him, but I couldn’t reach him. He probably changed his mind and gave the European account to another agency. I’m sure he had no idea the effort I made to keep that appointment.

Experiences like that teach you something. That job at Correos taught me that anything is possible if you’re willing to go for it.

How did you start collecting art?

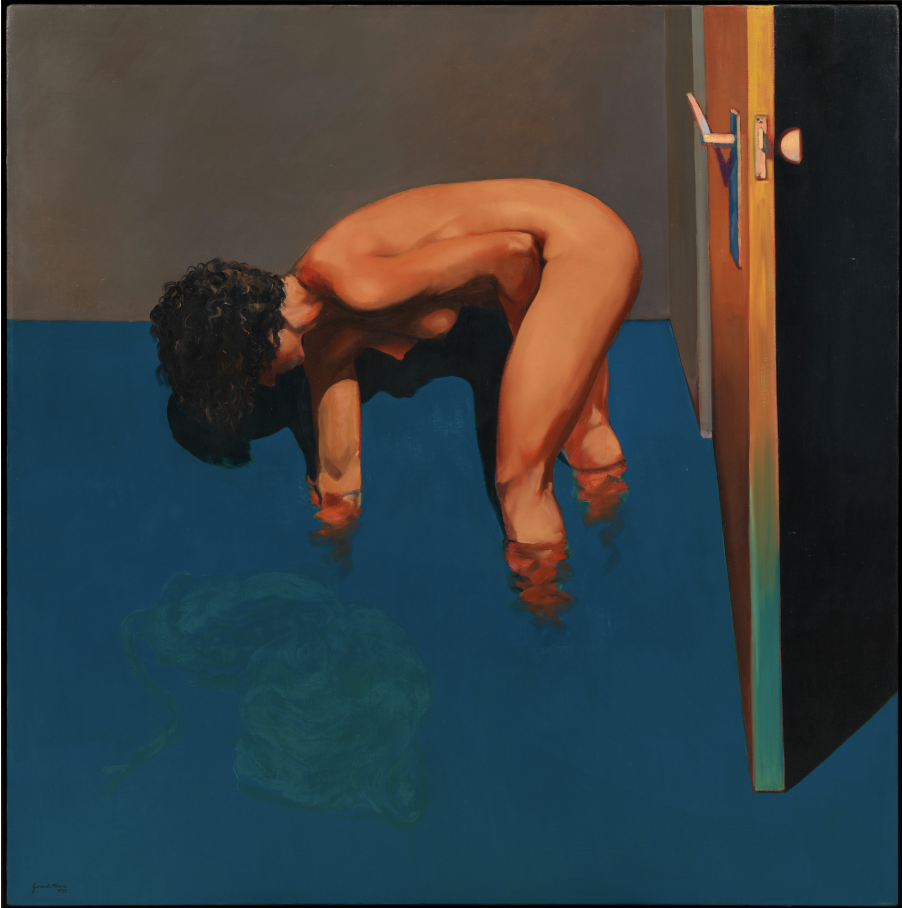

One day, while walking through Barcelona, I randomly walked into a gallery: Galería Adrià. A piece by Serra de Rivera caught my eye: a naked woman crouching with one hand in the water. The water reached her calves, and while that might have made sense at the beach, she was inside a room with the door open… and the water wasn’t flowing out. I was captivated. That mystery is what led me to start talking with the gallery owner.

It was 1973 when, together with some friends, we decided to invest in the Adrià Gallery. I bought 35% and convinced my friends to buy similar shares, divided among several of them. From the very beginning, I got deeply involved in the artistic side. We held around ten to eleven exhibitions per season, almost one every month, and I would buy the two best works from each show.

We had contracts with fourteen painters to whom we paid a monthly salary in exchange for artwork. But sales were never enough to cover the expenses. At the end of each month, Emilia, the accountant, would call me and say, “This month we’re short 100,000 pesetas.” I already knew there was no way to recover that money, so I’d buy another painting. It was a way to keep the project afloat and also to support the artists.

Eventually, one thing led to another. I became a gallery owner and collector at the same time, almost out of necessity. In 1980, Emilia called again, this time with a more worrying figure: 450,000 pesetas. I called my wife, Carmen, and asked, “How much money do we have in the bank?” She answered, “450,000.” At home, we had a thousand more, and in the savings bank, another thousand. I told her not to worry but that I was going to write a check for 450,000 pesetas. She was so gracious that she only asked, “Have you thought this through?” I told her yes, that at least I could say I had given everything for the gallery. We decided to keep going, even though we knew that if more money was needed, we’d have to close. And that’s exactly what happened — shortly after, we closed.

Before that, we had the luck that the neighboring space to the gallery became available. I suggested we take it as storage to free up the previous one, which allowed us to earn some money by subletting it. When we subleased both spaces, I gathered the partners — all of whom had more financial means than I did — and told them that since I had involved them in this business, I’d prefer that they choose whether they wanted the money we’d made or the paintings. They all chose the money.

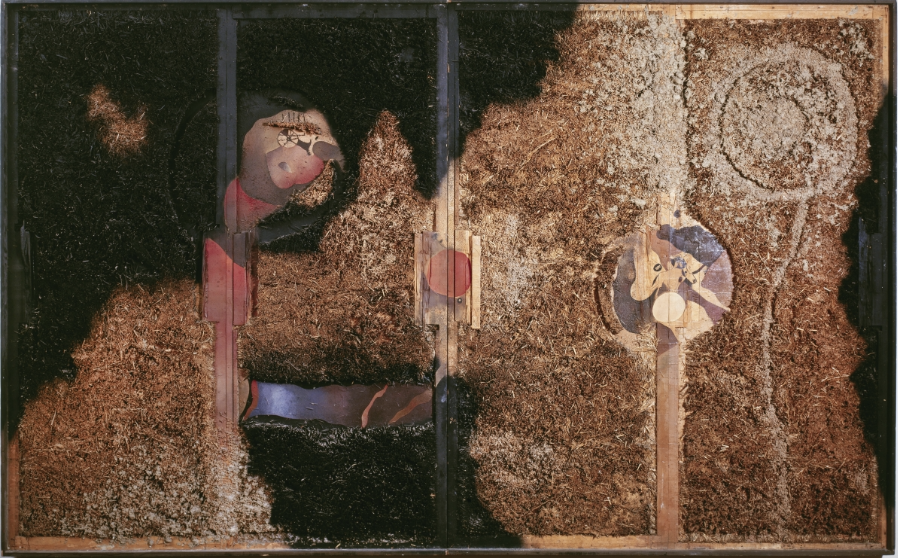

I kept the paintings. And there were quite a few. I already had over 200 works from previous exhibitions, and suddenly I found myself with about 300 more from the storage. I had 500 paintings. I had no place to keep them all. I spread them around my office, my home, and the house we had outside Barcelona… And Carmen, far from complaining, was delighted. We both shared a passion for artists, both figurative and abstract: Serra de Rivera, Guinovart, Ràfols Casamada, Hernández Pijuán… Even Canogar, from whom I recently bought a work at auction, which I believe was once exhibited with us at the gallery, or similar works.

What has been Carmen’s role in your life and in your collection?

Carmen and I met when we were very young, just 15 and 16 years old. Since then, we have done everything together. I always say that if I have achieved anything important in my life, it was with her by my side.

We went almost a year without buying art, and the situation improved. Then we returned to galleries and fairs. Carmen has a keen eye and great sensitivity. We liked both abstract and figurative art. The collection was shaped by our two perspectives.

We have a habit we love: when we arrive at an exhibition, we separate. Each of us explores the show at our own pace. And when we leave, we almost always agree. It’s as if we see with the same eyes, but from two different viewpoints.

We have visited many fairs. We had a stand in Basel with Miró prints that sold very well. That opened doors for us. We also went to ARCO, and on my work trips, I took the chance to visit galleries in New York, Paris, London…

She really enjoys art. At home, we have paintings everywhere: in the office, at the house outside Barcelona… And Carmen loves it. She enjoys art as much as I do. Carmen and I built the collection little by little, buying what we liked. And often, we coincided without even talking about it.

Which period do you remember most fondly?

Without a doubt, the 1970s. Those were the years of the gallery. I worked during the day at the agency, and in the evenings, from seven to nine, I went to the gallery. Then I’d return home to say goodnight to the children. It was then that I met most of the painters and sculptors who would become part of our collection and my life. There was a special energy. Everything was yet to be done.

In the ’80s, I was appointed to the board of directors. Everyone would leave at six in the evening, and I took advantage of that time to visit galleries.

On one occasion, I thought about donating a painting by Guinovart to the MoMA, the Museum of Modern Art. I met with the director, talked about the gallery, about Guinovart… but he literally threw me out. He told me that if he accepted a work from every painter or gallery trying to donate, there would be a line around Manhattan. I left devastated.

That night, at an Ogilvy dinner, I met a curator. I told her what happened, and she said: “You approached it all wrong. In America, you have to do it differently. Say you’re holding a competition between museums.” So I did. I visited the director of the Guggenheim and proposed competing for a donation we planned to make to an American museum. He asked if one of his curators could come see the work and meet the artist.

They sent Margaret Rowell, who came to my home in Barcelona. I lived in an apartment with an annex I used as a studio, and we invited her to stay there. She stayed three months. She chose three works by Guinovart and also wanted to meet other Spanish artists like Sergi Aguilar. She organized a wonderful exhibition with them in New York.

We even visited Marta Jackson, Tàpies’s gallery owner. A year earlier, I had told her about Guinovart, and now he was already at the Guggenheim with three pieces on display. Thanks to all this, he entered the American circuit.

And when we returned to Barcelona, Guinovart called me: “I’m waiting for you at the hotel.” I went, and he gave me a huge painting of his, almost four meters by two. We exhibited it recently in Zaragoza. It was a beautiful gesture. One you never forget.

Has art given you any life lessons?

Art has taught me how to truly look. Not just to see, but to really observe. To notice the details, the shapes, the beauty hidden in everyday life.

Recently, my wife and I celebrated our 60th wedding anniversary in Corfu, where my maternal grandparents were born. We found their house, with a plaque commemorating Albert Cohen, my mother’s cousin. It was very moving.

In Corfu, everything is beautiful: the olive groves, the coves, but also the doors, the windows, the weathered colors of the old houses. Art has taught me to see the beauty in all of that too.

What makes a work worthy of being shared?

A work of art has to provoke something. It must have quality, yes, but above all, emotion. There are pieces that, when you see them, speak to you, awaken a feeling. That also happens to me at the Prado Museum, not only with contemporary art.

I only buy if I fall in love with a piece. Even in museums, Carmen and I leave asking each other, “Which one did you like the most?” And we almost always agree on the most creative ones. Maybe it’s because I come from the advertising world. I’m fascinated by artists like Magritte, for that ability to imagine what no one else imagines. I also admire Miró, who can convey so much with just a few symbols. At home, I have a painting by Hernández Pijuán that represents a mountain with just a single line. Nothing else. But it has extraordinary power. That capacity for synthesis amazes me.

Sometimes it’s simplicity that I fall for, other times the strength of color or even mystery. Like the first piece I bought at the Adrià gallery by Serra de Rivera. That work is largely responsible for why Carmen and I are collectors today.

What does art give back to you?

Art gives me the satisfaction of seeing it. Waking up in the morning and seeing the paintings from my bed brings me great joy. We change them frequently, especially when we lend them for exhibitions, like the 49 pieces we just got back from Zaragoza.

I couldn’t live in a house without paintings anymore. At home, we only have a small part of the collection; there are artists I love but we don’t have anything of theirs hanging simply because there isn’t room.

Carmen and I almost always agree when buying. If it doesn’t convince both of us, we don’t buy it.

We share a sensitivity that gives coherence to our collection, despite its eclecticism. A critic once told me it was “too varied.” I answered, “I like abstraction and also realism.”

That said, there are things that don’t interest me. Some installations seem more like gimmicks than works of art. Like that banana stuck to a wall with duct tape, or an installation I saw in a U.S. museum where a sack dropped sand and formed a little pile on the floor. When the museum closed, workers shoveled it up, and the next day they replaced the sack. What can I say? Hourglasses already exist—I didn’t think that added much.

hat is your relationship with the artists like?

It has always been excellent. I like getting to know them, talking with them, following their evolution. It started in the ’70s when, from the Adrià gallery, we bought paintings because I believed in them. Without realizing it, that’s how our collection was born. Many have become friends. I even share personal moments with some, like going to football matches with Francesc Artigau.

We especially supported some artists. I took Guinovart to New York, organized an exhibition for him, covered his expenses… and when he returned, he gave me a painting that still moves me.

With Hernández Pijuán, we had a different kind of relationship: he didn’t want a salary, only that we pay him if we sold his work. Each one was different; some needed more support, others less, but with all of them, there was always a connection.

Today, I enjoy discovering young artists. Carmen and I still go to exhibitions and fairs, where we give acquisition awards: we commit to buying a work. One of our favorites is Marc Prat, who painted us with our eyes closed, and we have that painting above our bed. I exhibited it in New York, and there, a beautiful woman approached him and gave him two kisses: she was Leonard Cohen’s backup singer. She told me, “Don’t let Marc dedicate himself only to painting. He’s an amazing double bassist; I’m taking him on tour.” I was fascinated to see that Marc Prat is also a great double bass artist.

I’ve only had one bad experience: an artist to whom I advanced a lot of money and who never delivered the work. It hurt because he was a friend. But that has been the exception. In general, I really enjoy being with them.

How would you define your collection?

Our collection, as many have said and I admit myself, is eclectic. And it’s true. It includes abstract art, figurative art… always contemporary. I love eclecticism just like life itself. Life couldn’t be more eclectic. Sometimes I’ve even been criticized for it.

It’s very easy to buy art… when you like it. Carmen and I often agree. I remember a Zush exhibition with eighty drawings: I liked one, Carmen liked two, and one of hers was the one I liked the most. We bought both. That happens to us often.

We don’t choose themes, but I’m more attracted to people than objects. The human being is so rich in nuances and expressiveness that it always seems more interesting to me than any object. A contemporary portrait, even if distorted like Bacon’s, moves me more than a table. Although there are exceptions. At the Llavaneres Museum, we have an exhibition titled “Tables.” In one of the works, the falling tablecloth makes the piece seem abstract.

In fact, I don’t think we have many landscapes in the collection. Contemporary art doesn’t lend itself much to landscapes, or it does so in such an abstract way that it’s no longer recognizable as such.

I would like anyone who sees our collection to think: What were these two like, buying such different works? Well, that: “we like salty and sweet. The emotional and the rational. The powerful and the delicate.”

We have always bought as much as we could. Even a bit beyond our means. We have never had unnecessary luxuries. Our thing has been paintings.

That said, we have a large house in Barcelona and another in Llavaneres to be able to hang them. The collection grew more than we imagined. Today we have about 3,000 paintings, 1,000 sculptures, and more than a thousand prints.

The first work Carmen and I bought was in 1968. At that time, I wasn’t yet a partner in any gallery, but we already felt a strong interest in art.

Supporting young artists

What interests us now is discovering young artists. Since we appointed our granddaughter Noa, who holds a degree in Fine Arts, as the artistic director of our Foundation, we have focused even more on young artists.

Now that I no longer have the income I used to, we can’t buy paintings by great artists like before, but we continue. We set a budget and make an effort. At a recent edition of a fair in Madrid, we bought 17 paintings — all by young artists. Together, they didn’t even come close to the price of a Miró. It’s a collection built by looking, choosing, talking, and above all, sharing.

Which young artist have you recently acquired work from?

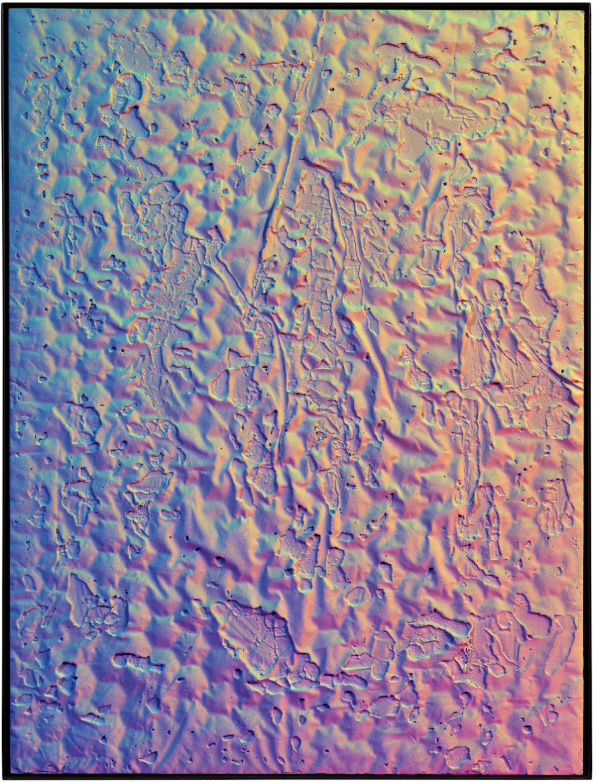

We have purchased a piece by the Australian Michael Staniak (1982).

What has been the most exciting exhibition you have done so far?

Without a doubt, the one we held this year at La Lonja in Zaragoza: “How We Built the Bassat Collection.” We prepared it together with our granddaughter Noa, in record time, and it was very special because we selected works that truly move us, with no other criteria than that. We were the curators. We gathered about 120 pieces that tell our story as collectors, from the 1950s to today. Seeing it all together, with that life and artistic journey, was deeply moving.

How would you like your collection to be understood in 50 years?

I would like that, fifty years from now, whoever sees our collection understands the taste that my wife and I had. That they look at it, judge it if they want, even criticize it if they want… but that it is able to convey our taste, what moved us. I don’t expect anything more.

If one day there is a museum — which could happen, because one of my daughters is determined that there should be one called the Bassat Museum — I would be fine with that. Maybe they could donate it to an existing museum if that museum dedicated a wing to our collection.

What has given you more satisfaction in life? Advertising or art?

Advertising has been my profession, and I have enjoyed it immensely. I started when there was still no formal Advertising degree in Spain; most of us were self-taught. There were very good advertisers like Paco Izquierdo in Barcelona and Roberto Arce in Madrid—both friends of mine.

I studied one year of Law and four of Economics, and I didn’t like them at all. Until I discovered a postgraduate program at the School of Engineers, where they offered courses like marketing, advertising, market research… I wasn’t a good student at university, but in the postgraduate I got straight A’s and two honors—one in Advertising and one in Marketing. The following year I was already teaching Advertising in that postgraduate program and also at ESADE. I studied intensely.

When I opened my agency in 1966, Spain had good advertising in print, radio, and billboards, but not on television. So I went to the United States to learn. Between 1975 and 1980, I went twelve times, each time for about six weeks, to Ogilvy. I learned a lot.

In my professional life, I haven’t only done advertising. I have helped improve my clients’ products and rejected advertising for others, like tobacco. I was chosen as the best Hispanic-American advertiser of the 20th century. Whether that’s exaggerated or not, it was an honor.

The 1992 Barcelona Olympic ceremonies also marked me. I directed 165 people for years. I didn’t set foot in the agency for seven months. It was a collective effort, but the ultimate responsibility was mine. We achieved enormous visibility.

Now, if you ask me what I’ve liked more, my profession or collecting art, I would say undoubtedly my profession. I have done it all there.

In art, I am a modest collector. Modest with a capital M. There are people who know much more: critics, museum directors… But I have lived art with passion. It’s just that advertising has been the axis of my professional life and where I have developed all my creativity.

What is your relationship between art and advertising like?

My relationship between advertising and art has been natural. One has nourished the other. Many art directors and advertisers are inspired by contemporary painters, and also by cinema. Contemporary cinema has been a constant source of inspiration for me. I have been lucky to meet great directors, like Adrian Lyne, who came to my office to make a commercial with me. He had won a prize at Cannes, and we wanted something in that style. In the end, it didn’t work out due to scheduling, but having him there was a luxury. I have worked with very talented people.

Now, where does my creative attitude come from? From a very young age. When I was twelve, I saw a movie that deeply marked me: Cheaper by the Dozen. It was about an executive at a car company in Detroit who applied the same efficiency methods at home as in the factory. He timed how long it took to get dressed, to button his vest… all to gain one and a half seconds. One and a half seconds! It struck me. That night I came home thinking, “I want to be like that guy. I want to improve how things are done.”

I asked my mother why we did certain things the way we did, and she said, “Because it’s always been done that way. Your grandmother did it that way.” That shook me. I wanted to try to do things differently. I was fascinated by the idea of optimizing, creating, improving.

I remember at home we kids slept in one big bedroom and my parents in another. One day, my parents decided that my brother and I should sleep in separate rooms, and I got a smaller room. It was an interior room, but I was delighted because I could read at night. And one day I wondered: why do houses have interior bedrooms? Why can’t everything be exterior?

With a compass and a bit of imagination, I designed a cylindrical building, with an elevator in the center and a spiral staircase. All the apartments were exterior. I went down to the street, counted the houses on the block, and realized the same number fit in a circular format as in the traditional one… but all with gardens around! Years later, the architect Coderch built four buildings next to El Corte Inglés in Barcelona with a similar concept. And I thought, “I can’t have been that dumb.” Deep down, I think I always wanted to be an architect, but a teacher told me I would never pass the drawing exam for architecture school.

Speaking of architecture and the city, what role do you think art plays in urban and social transformation?

I believe art must contribute to the transformation of the city. I’m not just talking about great muralists like Diego Rivera, who was an extraordinary artist (although not exemplary as a person), but about art as a real tool for beautification and urban identity.

It seems to me that if mayors made available to local artists those exposed party walls—because next to them there are vacant lots or green spaces where no construction will take place—and allowed high-quality murals to be painted there, not improvised graffiti, cities would gain tremendously in beauty. Those ugly walls, which were never meant to be façades, could become wonderful canvases.

How do you imagine advertising in the next ten years?

I believe that advertising in ten years will be conceptually the same, even if its form changes. Advertising concepts haven’t changed: advertising exists to sell a product.

This shouldn’t change. Hopefully, more and more campaigns will fulfill those three things, because we hold media in our hands that reach millions of people. If we don’t also use them to do something positive for society, we’re missing a great opportunity.

I remember a Prenatal campaign where, for the first time, we showed a father feeding his child with a bottle. Today, that wouldn’t catch anyone’s attention, but more than thirty years ago it was revolutionary. We also showed a man carrying a baby in a baby carrier… back then, that was unthinkable. Normally, you’d see the mother with a child in each hand and a baby hanging, while the father walked five meters ahead. Sometimes I wanted to say to him: “Sir, at least hold one of the kids’ hands!”

For me, if advertising can get ahead of what society will be like, facilitate change, show a businesswoman instead of the typical male director, that’s good for society… and it ends up being good for the brand too. That’s why I insist: ideal advertising is the one that sells, builds the brand, and improves the world we live in.

What advice would you give to a young creative in an era dominated by artificial intelligence?

If I had to give advice to a young creative in this era where it seems everything goes through artificial intelligence, I would say: exercise your personal memory. Use your intelligence, your capacity, your tenacity. Don’t give up if the idea doesn’t come immediately. Don’t rush to ask the chatbot for a solution. Fight to find the idea yourself.

I remember campaigns that took me months. In the Avecrem campaign, for example, it took me three months to come up with the “chup-chup.” I wrote over a thousand slogans and none convinced me. That’s how a good creative should be: demanding with yourself. You can’t say, “since I can’t think of anything else, I’ll stick with this.” No. You have to keep going.

I believe in personal intelligence. In effort, in conversations with the team, in brainstormings, in that shared work that leads to something original. And I have nothing against artificial intelligence — it can be useful. But it’s unlikely to create something truly new. It takes data from what already exists. It can combine, yes, but for me, today, the spark is still in people.

Besides, I like it that way. I like the idea to come from my head or from my collaborators’ heads. Not from an algorithm. Maybe it’s a generational thing, I admit. But I try to pass this on to my children and especially to my grandchildren: think first yourselves. And if you’re going to use AI, at least know well what you’re going to ask it. Do the work. Don’t delegate everything.

It’s like that first job I had at the post office. Very tough. Carrying sacks all day. But I stayed. I learned. I got to know myself. And in the end, when everyone else quit, I was the only one who finished. And the only one who got paid. You don’t always have to look for the easy way.

What do you say to the new generations?

That they work hard, that they make an effort. That they live through tough experiences that teach them the value of things. That they don’t always look for the easy way out. For me, carrying sacks at the post office made me understand that everything can be done. And after that, you’ll appreciate anything else.

Is there any project or dream you still want to accomplish?

I want to do a worldwide campaign for peace. It’s one of my pending dreams. I’m working on it.

I believe that today, more than ever, it’s necessary to raise our voice for peace. With wars in the Middle East, Ukraine, Africa… I feel even more committed. I am a strong defender of dialogue. I truly believe there isn’t a single square meter of land worth as much as a human life. Not one.

Fighting over a piece of ground, someone dying because of it… I can’t conceive it. I believe in reason, in words, in argumentation. I’ve only stopped dialoguing with impossible people—and very few.

I’ve tried to maintain this spirit of dialogue even in the professional world, although I admit there have been moments of rivalry. I remember an anecdote with a great creative who had a small but excellent agency. He told me I was copying him, following him. I replied that no, I wanted to build a big and creative agency, not just a creative one. He didn’t understand well, and for years I know I wasn’t exactly his favorite person.

However, recently, in public, in front of several colleagues, he said: “Do you know what the mistake of my life was? Not partnering with Luis Bassat.” And he said it sincerely, without need. It moved me. Because it’s not easy to admit that, especially in our sector. And because, although we competed fiercely, I always respected him. That someone says something like that after so long filled me with pride.

What would you do if you were born again?

I don’t know if I would go back to advertising. It has changed so much with social media and computers that maybe I wouldn’t like it as much anymore. But one thing I’m sure of is that I would definitely collect art again, without a doubt.

Even now, at 83 years old, I still get moved by works from young artists. And if I can, I buy them. I like to exhibit them, to share them. At the last show at Nave Gaudí, I displayed works by emerging artists I had discovered at fairs in Madrid. During ARCO week, I spend an entire week touring the city and its galleries.

I remember a work by a young English artist: 40 concrete blocks sold separately. But to me, it made sense as a whole. I bought the entire series. When exhibiting it in Zaragoza, it was shown alongside sculptures by Henry Moore. The artist was moved: “To have my work here, next to Moore’s… you don’t know what a favor you’ve done me.” And that favor, which was his, I also felt was mine.

Those moments are priceless. And I believe that is part of what collecting means to me.

What would you say to them, to the emerging artists who are out there fighting?

I would tell artists to get moving, to look for opportunities abroad, to write to galleries, to use the internet. Today it’s easier than ever to reach other countries without leaving home. You have to go where the client is.

Right now, there are artists from Barcelona who are selling in Madrid because the market moves more there. You have to go where the client is.

I collaborate with a young digital agency, Annie Bonnie. They know a lot about the internet, but they ask me to help with what I know: understanding the consumer, building a brand.

Through our foundation, we also use technology to support artists: we include QR codes on the back of paintings, also next to those on display, so whoever sees them can learn more about the artist, see other works, and even buy them. We don’t sell, but we do want to help them sell.

If I were born again in the age of social media, the first thing I would do is learn those tools well. Like when I went to New York to learn about television, because here it wasn’t done well yet. I wouldn’t fall behind.

It makes me very sad to see very talented artists having to give drawing classes to make a living. And part of the blame is political.

‘Art has taught me how to see’, says Luis Bassat. One of the great lessons from this conversation is to learn to look with different eyes, with attention, with sensitivity. An invitation to let ourselves be transformed by what we see, by what we feel. Because, as he well knows, truly seeing is the first step to understanding, creating, and transcending.

Thank you very much, Luis, for sharing so much.

MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE COLLECTION

The main venue where the Bassat Collection can be visited is the Nave Gaudí in Mataró, an iconic building designed by Antoni Gaudí that has hosted exhibitions for years in collaboration with the City Council. Various stages of the collection have been showcased there, from its beginnings to 21st-century art, combining painting, sculpture, printmaking, and installation.

In addition, they organize traveling exhibitions both in Spain and abroad, bringing Spanish contemporary art to new audiences in cities such as Sofia (twice), Warsaw, Krakow, and New York. To stay updated on upcoming exhibitions, you can visit their website: www.luisbassat.com.

The Foundation also collaborates in social initiatives in Africa: in particular, it has supported projects focused on education, health, and improving facilities for children and women in southern Mozambique.