ACdO Interview

We talked to the founders of ACdO about their successful projects as PET Lamp based on social, cultural and environmental commitment.

Álvaro Catalán de Ocón, winner of the National Design Award 2023 in the professional category, awarded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation, Enrique Romero de la Llana and Sebastián Betanzo form ACdO, the acronym for Autoproducción y Comercialización de Objetos, three entrepreneurs who have achieved the global from the periphery by applying social commitment and ancestral craftsmanship from the idea of sustainability. And they have done so in an organic and natural way in the light of their star project, PET Lamp, which has been shining for a decade.

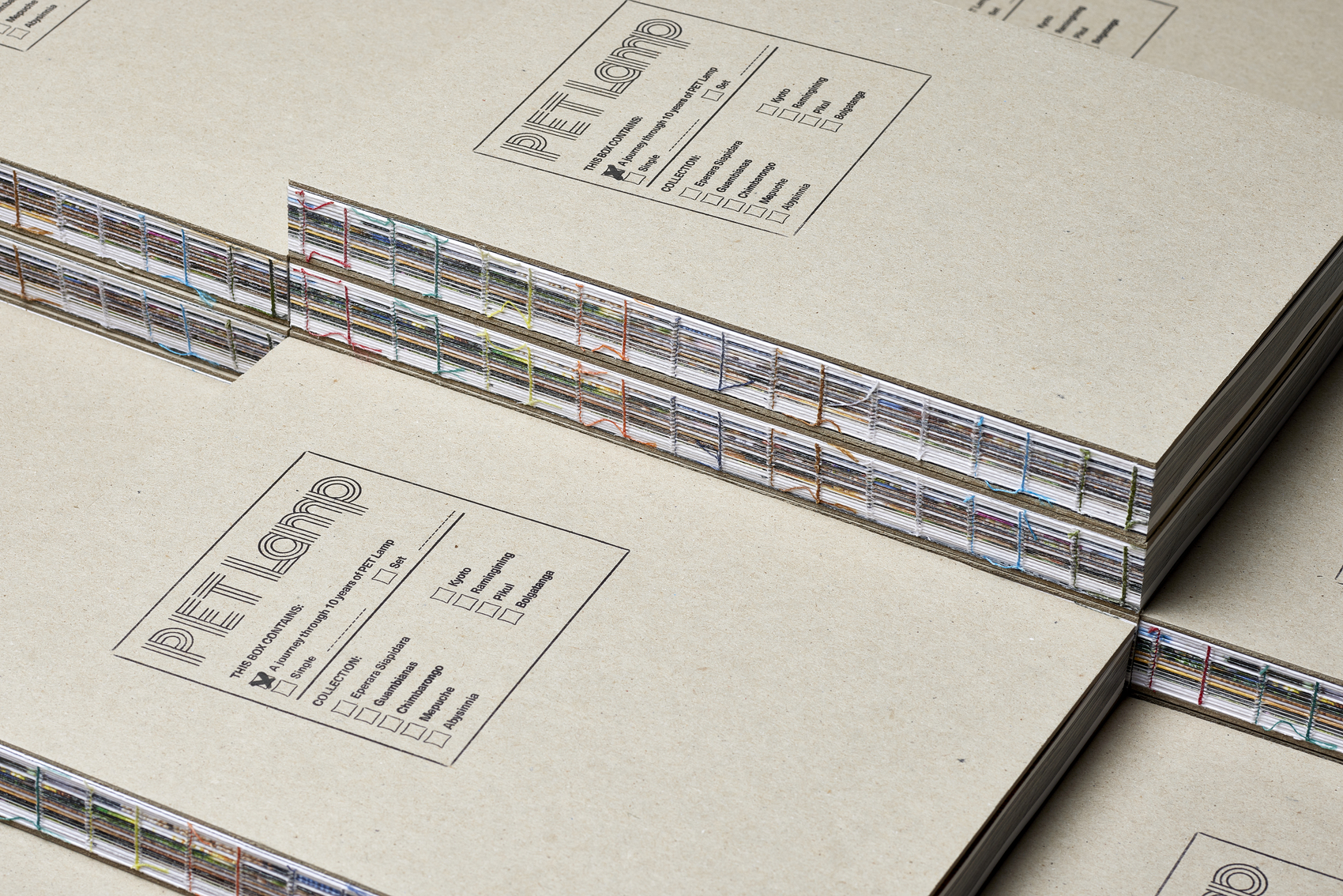

These lamps, the result of combining traditional basketry and the reuse of PET plastic bottles, have been in galleries such as M+ in Hong Kong or Rossana Orlandi and in museums such as the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne (Australia), the Design Museum in Barcelona, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (MAD) and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, among other prominent design and art centres. The data that endorse both their presence in the world and the social and economic impact they have generated are overwhelming and are illustrated in a very didactic way in his 300-page book entitled A journey through 10 years of PET Lamp.

They visit El Invernadero to tell us how they have been transforming themselves from very different backgrounds: Álvaro and Enrique have a background in design and Sebastián in economics. They also belong to different generations and have been combining their knowledge and work until today to continue contributing brilliant ideas to the world of design and to illustrate a way of life and an attitude towards it.

First of all, congratulations on the national award, what does this recognition in our country mean for ACdO? How are you experiencing it?

ACdO (Álvaro Catalán de Ocón). With the telephone like a popcorn machine, we have always worked on design from the periphery, I came from Barcelona, I opened the studio in Carabanchel, to work with artisans, in self-production and outside the industry channels. I’ve always liked to be on that intermediate line of things and that this is valued, and from the Ministry of Science and Innovation it’s very important, because design has always been in no man’s water.

What are the beginnings of ACdO like?

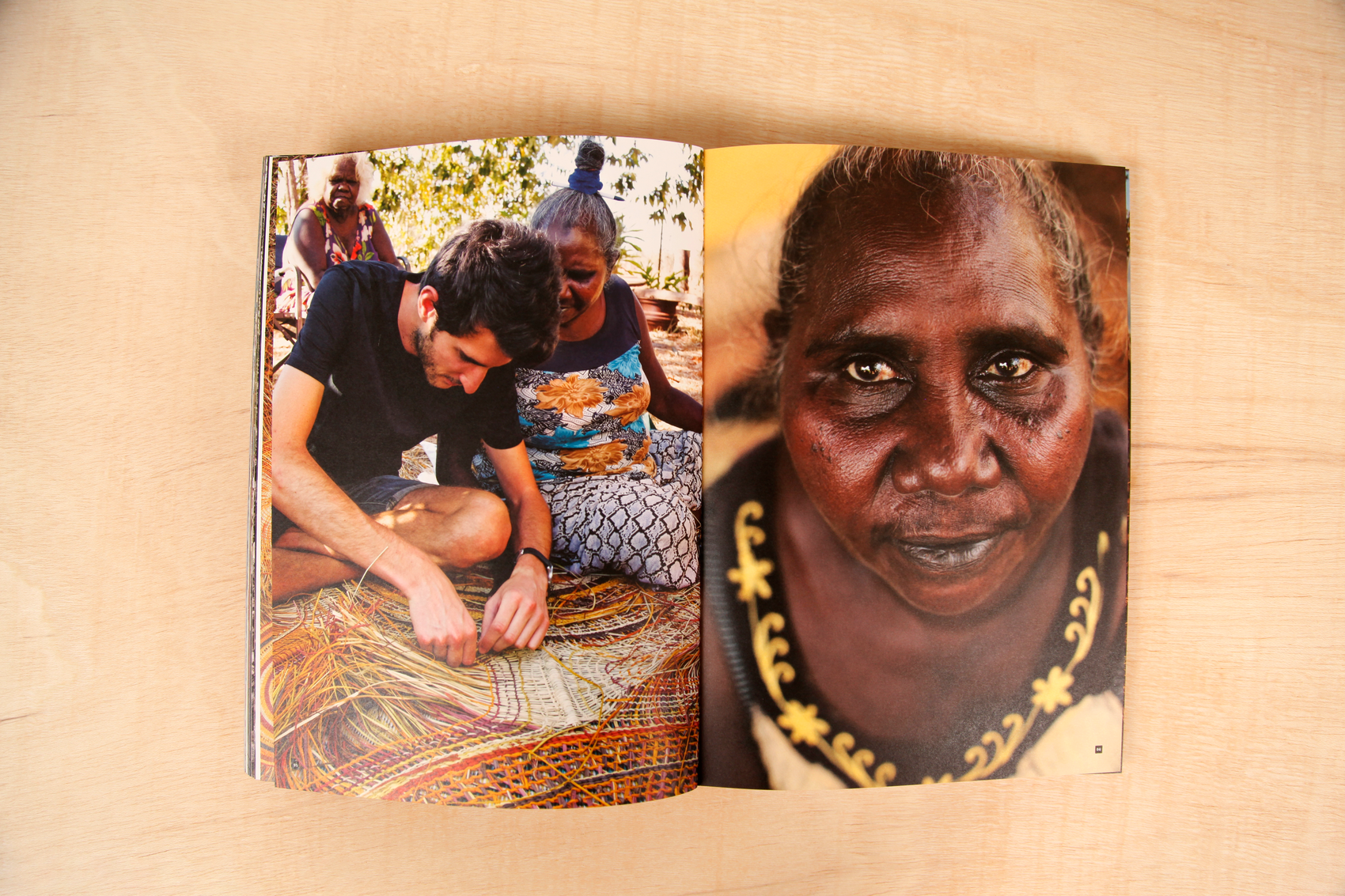

ACdO. It all started in 2011, when I travelled to Colombia for the first time, the first prototypes were made in Madrid and Enrique joined the team as an intern. The PET Lamp project remained on standby until 2012, when we held a workshop in Colombia and the process was completed with Sebastián, who, in addition to our design potential, provided the financial support to cover the three pillars: sales, product and design. From there, projects such as Eperara-Siapidara (2012), in Colombia; Chimbarongo (2013), in Chile; Abyssinia (2014), in Ethiopia; Kyoto (2015), in Japan; Mapuche (2016), in Chile; Ramingining (2016), in Australia; Pikul (2018), in Thailand; and Bolgatanga (2019), in Ghana.

SB (Sebastián Betanzo). ACdO was born from the PET Lamp project and seeing the success it generated and the attention it received from the media we decided to use it as a platform that transformed into what we are now. After 5 years focused 100% on PET Lamp, when we saw that it had gained momentum, we came up with the idea of bringing out Álvaro’s previous products to move them. Having different training, being from different generations and having a different approach to the industry generated a holistic and complete vision.

ERdL (Enrique Romero de la Llana) When ACdO was born 5 or 6 years ago it didn’t work as we expected. ACdO’s profile is more exquisite in detail and sensitive compared to PET Lamp, which is more popular and leaves the rest of the products in the shadows. That’s why we want each product to find its own way. Every year we try to launch a product and in 2023, instead of launching another lamp, the product has been the PET Lamp anniversary book which took us eleven months to edit.

Why was it born with such a different profile to other design studios?

ACdO. With the crisis that emerged in 2008, which affected all areas, this world of creation underwent a transformation in the way of understanding 20th century design and, as a designer, I didn’t feel capable of joining that sick rhythm of producing, selling, applying marketing ideas and starting again, that’s why I opted for self-production and never worked for anyone.

ERdL. For us the approach to the local partner is very important and we get involved in keeping the workshop going when we leave. In the beginning, we chose a country, now they call us. For example, in Ethiopia it has been through the wife of a diplomat and now we are talking to a Spanish woman who works with an NGO in Uganda.

SB. Working in this way is logistically very complex and it is necessary to apply quality control and, for this reason, a filter is vital. It is not the product that is important but the project that involves artisans and many more people, and we need to be attentive to social commitment and ecological issues, which is why we always have a leg in the country where we work, an interlocutor for the satellites created in each country.

You have just presented Plinto at Maison & Objet, which was born as a very ethereal object, how has it been received in Paris?

ACdO. Plinto has the magic of seeming silly. It’s beautiful and it’s one of the most poetic because it was born when in pandemic you saw the weeds growing freely in the city and that made us learn to enjoy the details and to value the little things. It was born to praise something as insignificant as a weed, it first appeared as a Christmas present, it was well received and we decided to launch it as a product.

ERdL. It is dispensable and yet everyone falls in love with it. It’s our most immediate project and we love talking about Plinto pieces because there’s nothing to say, it’s a very atypical product in our catalogue but the production was a challenge because of the packaging and the price, we had to find a formula to turn it into a market object.

SB. The product is not very functional and yet the packaging is very functional. In Paris it has been very well received because it is a product with a lot of appeal, in the studio we have hired Iván Vidal to manage PET Lamp and we can dedicate more time to ACdO, because after celebrating the 10th anniversary we thought we had to give ACdO a boost and, in this case, we have done it through Plinto.

It’s been a decade since PET Lamps appeared and, as Ikko Yokoyama says in the book, “it will evolve over the next ten years as it constantly reflects the changes of our times”, where is it heading?

ERdL. Because of its solid and well-formed structure, we want it to grow to produce and sell more so that it develops and flies. Right now, we have many collaborative projects open in Ghana, Rwanda, Uganda, Sri Lanka and Nepal. They have come all at once and we want to avoid filling the PET Lamps catalogue without a why but because they are enriching projects. Moreover, the intention is to get out of the suspended format.

ACdO. We have been directing it and we want to let the project go by itself. I like to say that it is a wave to be surfed. With these five workshops on the table, it is necessary to see how to manage them, what emerges and to open up different strategies, for example, by giving commercial or design support or other factors, without generating expectations. We have a broad vision of crafts and our point of view already has a value in itself, so we can do more curatorial work, for example in Sri Lanka.

Why do customers choose PET Lamps and what makes you different?

SB. At the beginning, we thought that PET Lamp would be around for 5 years and it turns out that the focus is not only to manufacture lamps but something more social and ecological and we can dare to do more, the brand already has a sound and a value. We have created a school on a type of product. Those who imitate us do not treat people and the environment well, we have the B Corp certificate, the UL and CE Safety Mark (obligatory for marketing in the European Union). Suppliers must be treated fairly and with our projects we support craftsmen for years. That is our differentiation.

ERdL. The first reason why someone buys a PET Lamp is ecological or social, they are making a purchase that reinforces a consumer mentality and satisfies a need. Mostly, it is a female public, between 35 and 40 years old, who have given a lot of thought to buying the lamp and who buy it in an aspirational way. Our private customers are our best ambassadors because they know the product very well. There are lamps inspired by ours, but we make them in such a way and with so much effort behind them that they are impossible to replicate.

ACDO. PET Lamps are emotionally charged and the product conveys this.

What are the projects you are working on now?

ACDO. We are working around three development channels: one is the American hardwood cloud exhibited at Matadero and made for the American Hardwood Export Council’s (AHEC) Natural Connections project, presented with other designers at Madrid Design Festival, which may be produced for an art gallery; two, a project for a Spanish brand that we cannot yet reveal; and, third, a prefabricated house for me.

ERdL. The ACdO building is a symbolic element, which won a Mini Award at the Madrid Design Festival, and has a desire to implement what we were talking about in that award presentation, ideas such as social or environmental circularity, improvements in insulation, and that is what we have in mind to develop, the idea of the building as another ACdO product. As PET Lamp flies by itself, we can simply accompany it and, in the next ten years, the project will generate more initiatives, where we are curators, so that we can dedicate quality time to the rest of the products.

SB. There are new products and latent designs that revolve for example around La Flaca, Candil, Rayuela, Riad… ACdO develops products in an intuitive Self Directed Project way, that is to say, without briefing, but just seeing what would fit.

Design is a very powerful tool, do you agree with this idea?

ACdO. The designer is a bit like the architect, whose humanist role is to bring together all the needs because he is not a specialist, without being an expert in ceramics, lighting, etc., he comes to all of them with new eyes to give them shape.

SB. We understand design as support to solve a problem and, for example, PET Lamp is not so much the design exercise but the structure that is set up to do it with the artisans and all that it entails, and to do it so that it works in a sustainable way. That is why for us it is very important to think about all the processes that accompany it, such as the social or business improvement of the artisans or the inhabitants of the area where we develop it.

ERdL. Design can satisfy pragmatic needs but that is not our niche because we aim to cover humanistic needs that touch on feelings. It’s a bit more difficult to identify but it’s our driving force. For this reason, we talk about projects and not products.

What does the future of design look like from your point of view?

ERdL. It is a tool to make us reflect more and consume less and it has to focus more on a critical and vindictive point of view so that it doesn’t feed the throwaway industry and consumerism. We created the Plastic Rivers rug collection for GAN Rugs, made with 100% recycled PET.

SB. The challenge of design is to be able to make a product that implies a solution to a problem and that takes climate change into account, that is connected to reality.

Given the current climate situation and your social and environmental commitment, do you think that design has to be sustainable or will it be a failed design?

ERdL. Fortunately it is a given, but it is another matter if it is implemented well. For example, greenwashing is criticised, but you have to start somewhere. At present I would like to think that there are things in this sense that are not tolerable.

SB. The problem is that the environmental cost is not usually taken into account and should be reflected in the price, which is a figure that often tells us how innocuous the product is.

The ACdO building, is it just another design, what is its evolution, and what projects do you have for this building if they can be brought forward?

ACdO. In our headquarters we have created an ecosystem that is a product in itself, it communicates a lifestyle, like the space designed by the Dutch designer Piet Hein Eek, it is our reference point, we would like to become like that and for it to be understood. We want to generate noise and be in interesting proposals, for example, we are present in Open House, soon in Luz Madrid… some are altruistic but we want to nurture a model that helps to make visible creative people who need it. We like Marisa Santamaría’s idea of us as cultural agitators. As well as designing things we want to be part of a movement.

Álvaro, your designs speak of austerity, simplicity and imperceptible details, why? Does it have to do with your idea of the peripheries or what is it associated with?

ACdO. I see them as properties of the designer’s profession, as the German designer Dieter Rams also said, and those principles have a lot to do with it. The design has to be as minimal as possible, as small as possible because, for me, these are characteristics that are more characteristic of this discipline, while the excessive, the anecdotal or the mannerist I believe correspond more to the decorative arts.

Part of the limitations I place on myself as a creator is that they should be reproducible, that they should not be unique pieces, nor am I the one who makes them, that’s why we self-publish and are not makers. Reductionism is another of the values we apply in the studio, that is, to make design, with respect to other creative and artistic forms, reach a point where you can neither add nor subtract anything, achieving a certain objectivity until you reach the essence of what you want to do. In this sense, I greatly value the austerity of design and that reaching the form, not looking for it.

Speaking of the decorative arts, except for the one in Barcelona, there is no design museum as such in Spain. How do you see this lack when Spanish design is such an important phenomenon?

ERdL. I think there is a problem with the ‘Spain brand’ concept that design suffers from like other fields, among other things, because each one rows separately and there is a lack of unity as a country. It happens with other disciplines. It’s good that there are local design identities but I think that this umbrella is missing, perhaps it is also part of this Spanish identity that it is difficult to generate this more abstract brand, I think that maybe that’s why this museum of Spanish design is missing. To begin with, there would always be the problem of where to put it, although solutions can be found.

ACdO. In my opinion, as happens in the art world too, those big national museums should have headquarters, for example, in Barcelona, Seville, Bilbao so that the collection can rotate, it would seem to me the most logical thing to do. On the other hand, it’s good to decentralise, but not so that only the very expert can go, but to be able to maintain a vocation for dissemination. Or, it could also be that the city tends to be related to the discipline, like Arles where photography has marked the character of the city. In Barcelona this is clearly the case with design.

Madrid would lend itself to a museum of architecture and design, two professions that are more closely related than art and design, as happens when you go to the Pompidou where you find art, design and architecture. A museum of art and architecture in Madrid would come in handy. Apart from the fact that, until the 1950s, the profession of designer was mainly exercised by architects. It is also very difficult for the design museum not to look like a shop. In the Textile Museum in Holland, for example, what they did was to empty it of building work and fill it with looms and machines and now it’s like a workshop where people go to design their fabrics because they have an archive to draw inspiration from or to see the machinery. That is to say, it has become a living place of production and perhaps museums should also aim to do that, not just dedicate themselves to conservation.

SB: For me the difficult thing would be more than where to place it, what to show of design, how far it goes, to define what is the umbrella for what is design and what is not.

ERdL. Some book collects the great Spanish inventions, anonymous things that nobody knows are Spanish, such as the submarine, the mop, the BIC pen or the lollipop. I would start by rescuing the names of the creators of these anonymous and international objects as a good starting point.

Do you think it also happens with architecture?

ACdO. Madrid deserves a museum of architecture because architects from Madrid, for example Alejandro de la Sota or Miguel Fisac – the latter did some very radical things – are not as well known as they should be outside Madrid.

ERdL. There is the ICO Museum, which does this function, but there is no public fund. Then there are events like Madrid Design Festival that are phenomenal and it’s a multi-year project, with an organisation, an objective, but it’s a private initiative that can disappear if it loses sponsors or lacks municipal support, and that would be a shame.

Ceramics, textiles, metal, natural fibres in the form of lamps, small furniture, lighting, accessories, what do you still have to design? Is there anything you would like to come up with?

ERdL. I would say something perhaps more digital, we are very offline, we like the material, the tangible, the pure materials, honesty… and there is another variant of design of creating much more from models or that the work ends up being a NFT, in other words, I think there is a field that personally doesn’t attract me much, however I think it is the furthest thing from our way of working that there is at the moment.

You have been focusing on PET Lamp, the last year has been dedicated to the production of the book which is just another product, is there anything you have up your sleeve?

SB. Perhaps redesigning the products that we already had and that sometimes for different reasons, for example with the case of La Flaca, which technologically has undergone a change that implies redesigning it.

ERdL. To give continuity to other projects.

ACdO. In this sense there is always talk of having to design a chair, THE chair, and it’s a gap that is there and that gives a lot of respect and that as the situation has never been considered as if one day it doesn’t occur to you to wake up and say I’m going to design a chair, but if they don’t ask you to do it, it’s difficult. The chair is a challenge, it’s like a micro-architecture. What happens is that, on the other hand, there are so many chairs, in the catalogue we have the Home Office that we made with embroidery based on the Aluminium by Vitra and it makes us wonder why design another chair.

What would you say to young designers or entrepreneurs in the world of industrial design?

ACdO. I think I see a lack of passion because they see design as a job and I can’t separate it from my life. I get the feeling that there’s no such thing as giving your all as we have done. I encourage you to convert it and integrate it into your passions and your life, taking it to another dimension. Mariví Calvo, from LZF Lamps, who together with Sandro Tothill, have turned a job into a way of life, of understanding the world, connecting with people everywhere, travelling and doing so many other things that don’t follow the idea of business, which is the negation of leisure.

Our business is not the most profitable one we could have chosen but it has been profitable in other ways and today I think there is this vision of dont work hard work smart. I agree with the philosophy that the effort itself is worthwhile, even if it doesn’t take you to a certain place or to a wall that makes you go backwards, that path has already been worth it. This is something that is not seen so much today, the younger generation wants immediacy.

ERdL. I point out that immediacy also seems to be the cancer of the generation of 20 year olds that affects them at a work level but also at a vital level. It’s a generation that lives a bit like a disappointed generation with a lack of constancy that throws in the towel at the drop of a hat.

This frustration is very noticeable at work.

SB. It’s difficult to give advice because in the end some people not only don’t get excited about their work, but they don’t even get excited about life or a hobby to which you can dedicate yourself in depth. It is difficult for someone to be willing to bet on the long term. It’s risky and not very rewarding at first and in the end it’s an exercise in understanding oneself before starting a journey, but people are not even willing to pause and reflect on what they really like to do.

We have a culture of having to go through stages without pause, from school to university to work, and in this process there is no time to take six months to think, to travel, to get to know, to read…, they don’t give you that time and the crisis arises when you fill in the gaps.

Do you think it is an education-related issue?

ACdO. Now we are having problems in the studio with hiring interns because you have to do it through a university, you can’t have an intern coming out of school and wanting to have the experience of working in a studio before getting into a design university.

SB. We had an American student, who comes from a different education system, who was thinking of studying design and wanted to come to Spain to see if she liked it… She turned out to be the best intern we’ve had without any specialised training because the key was the attitude that can determine success. You learn the aptitude, but the attitude is either instilled in you when you’re a child or you stay there.

ERdL. At 17 or 18 years old, this grant holder had taken a design course at school, had won several photography competitions, in other words, she was very well supported. Indeed, you can’t learn attitude, you have to nurture it.

Editor: Beatriz Fabián

Beatriz is a journalist specialising in offline and online editorial content on design, architecture, interior design, art, gastronomy and lifestyle.

Photographer: Nieves Díaz.