Interview with Lola Barrera, from Debajo del Sombrero

We spoke with one of the founders of Debajo del Sombrero, an artistic platform that supports people with intellectual disabilities in developing their artistic practice.

Debajo del Sombrero was born from what Lola Barrera defines as a “heartfelt connection” to art brut and outsider art. This is how she describes her love for art created by people with intellectual disabilities. A family doctor by training, she practiced for ten years in the Basque Country, took a leave of absence to devote herself to painting, and for almost two decades has focused her work on this project. It all began after reading an article about the artist Judith Scott in a magazine published by the Down Syndrome Foundation. “This has to happen here,” she thought. In 2007, together with Ester Ortega, Amanda Robles, José Antonio Sacaluga, Isabel Altable, and Luis Sáez, all with experience in the fields of art and intellectual disability, she founded the Debajo del Sombrero Association. The final spark was a film that Lola shot with Iñaki Peñafiel, an experience that would set the course for the project. Debajo del Sombrero is now 18 years old and has established itself as one of the most unique projects on the Spanish artistic and cultural scene. We spoke with her to learn about its origins, philosophy, and present.

You have been operating for 18 years now. For those who don’t know you, what is Debajo del Sombrero?

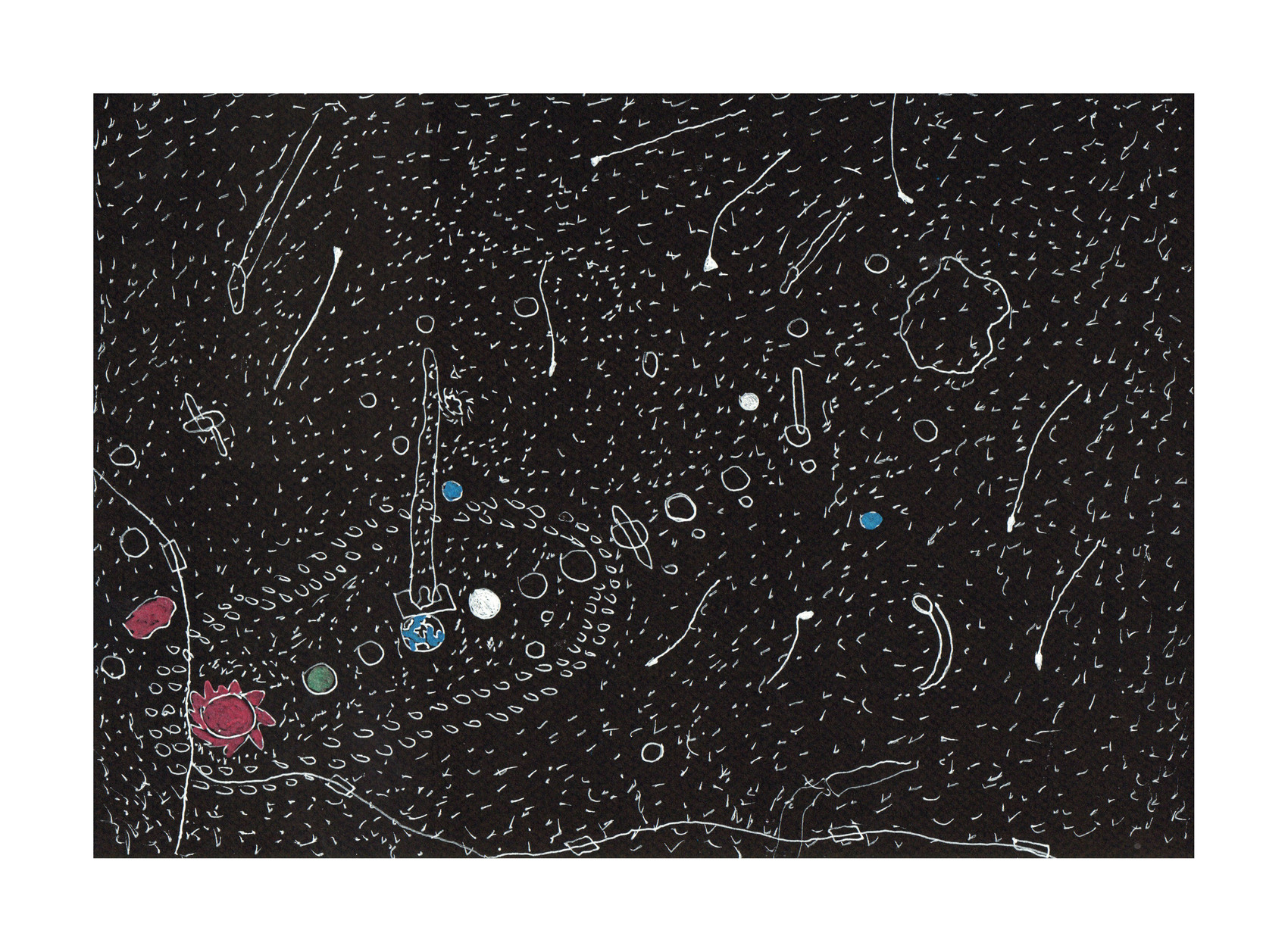

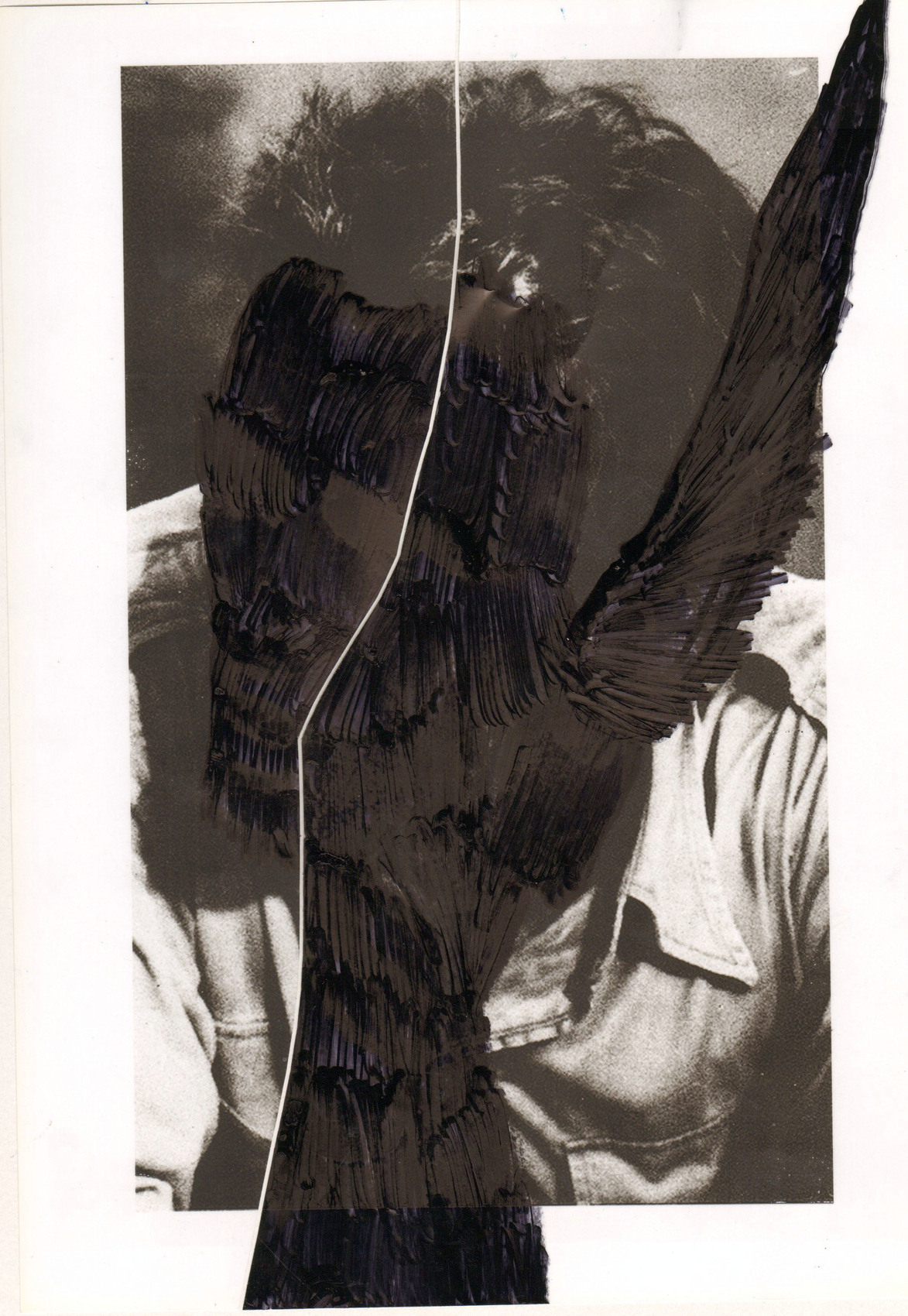

It is an artistic platform that supports people with intellectual disabilities in developing their artistic practice throughout their lives. It is not about one-off workshops or recreational activities, but rather in-depth and sustained work, focused on the development of their own artistic languages and on considering these people as contemporary artists.

The project is based on listening, attention, and absolute respect for individual processes. It also involves giving public exposure to the works: exhibitions, residencies, archiving, dissemination, and care of artistic production.

The origin of the project is diverse, because each of the founders comes from different experiences. In my case, the starting point was a film I directed and shot in 2004, which was released in 2006. It was about an American artist with an intellectual disability, and through her I got to know other centers and artists. It was my first contact with this type of artistic language, and I fell completely in love with it.

The name of the project is very meaningful. Where does it come from?

It comes directly from that film, which was called What’s Under Your Hat? The main character always wore increasingly larger hats and headdresses. At one point, someone asks her what’s under her hat. That question is very beautiful because it speaks of looking beyond the visible, of not staying on the surface. We took that title and transformed it into Debajo del Sombrero (Under the Hat), because it sums up our way of seeing things very well.

Who are the founding members of the team?

Luis Sáez, Isabel Altable, Ester Ortega, Amanda Robles, and José Antonio Sacaluga. We all come from the world of art; some had experience in autism centers or working with people with intellectual disabilities, others did not. In my case, the key experience was the film, which completely opened my eyes.

How did it all begin?

After the film’s release in 2006, it had quite an impact: festivals, television, reports. I felt that something like this had to exist here, although I wasn’t quite sure how to go about it. Through an article about the film, I connected with people who worked with individuals with intellectual disabilities and shared my concern about moving away from a welfare-based approach.

This brought together other people who were already working at the intersection of art and disability. Among the founders is, for example, Luis Sáez, the project’s artistic director, along with professionals linked to centers for autism and intellectual disability. We all shared the desire to create a truly artistic space.

What was the next step for this artistic platform?

The seed for the project was planted after the film’s release. Following a television report, I thought that Spain should have something similar to the assisted art studios I had seen abroad. The project began at Matadero Madrid, with an initial group of 17 people with very complex profiles.

What was the working philosophy from the outset?

The basis has always been attention and support. Being attentive to what is happening, to what each person is doing, and supporting that process without imposing anything, without intervening in an invasive way or superimposing what one already knows or thinks should happen. Time is essential: each person needs their own pace for their language to emerge.

The following year, we began collaborating with the Faculty of Fine Arts thanks to a research project led by José Luis Gutiérrez. Since then, we have been working in three main spaces: Matadero Madrid, La Casa Encendida, and the Faculty of Fine Arts. Each one fulfills a different function within the process.

Do you help them to pursue a more academic education tailored to their particular needs?

Yes, but always based on what each person brings to the table. We do not impose a traditional academic education, but rather seek resources that are adapted to each process. For example, we work in collaboration with the Faculty of Fine Arts thanks to a research project called Art at the Service of Society—now directly linked to the dean’s office of the Faculty—which allows artists to have access to spaces such as sculpture workshops.

The key is accompaniment: being attentive, not intervening excessively, not superimposing our knowledge, and allowing language to emerge slowly and authentically.

Do you only work with artists from Madrid?

The workspaces are in Madrid, but the project has an international dimension. We have worked with European studios and developed artist residencies. For several years, we promoted a project called El territorio del artista (The Artist’s Territory), in which artists lived together for a few days in other contexts, always in dialogue with other artists.

How many artists are you working with right now and what is their profile?

We currently work directly with 38 artists, a necessarily small group, as the support is intensive and cannot grow indefinitely. They are residents of Madrid, although their reach is national and international. Some have exhibited in cities such as Berlin, Paris, and London and participate in international festivals and projects. These are artists with intellectual disabilities who develop a solid and personal contemporary practice.

How do you select artists?

The main gateway is the La Casa Encendida workshop, in which between 15 and 16 people participate. Every year in May, a selection is made. The criteria are not technical or academic, but deeply human: we value interest, perseverance, the emergence of a seed of personal language, and the possibility of long-term development. After one, two, or three years, some people move on to the studio. Once inside, their stay is indefinite: it becomes their artist’s studio.

How does your work differ from a one-off or recreational artistic activity?

The difference is fundamental. Many proposals for people with intellectual disabilities are based on occupational or entertainment activities. We believe that true cultural inclusion means taking what these people have to say very seriously. It is not a one-off activity, but rather accompanying an artistic practice throughout the creator’s life.

What does this long-term support involve?

It involves always being there: supporting the processes, taking care of the work, archiving it, promoting it, exhibiting it and, when appropriate, selling it. An artist with an intellectual disability cannot do all this on their own. They need a studio to support them. That is our role.

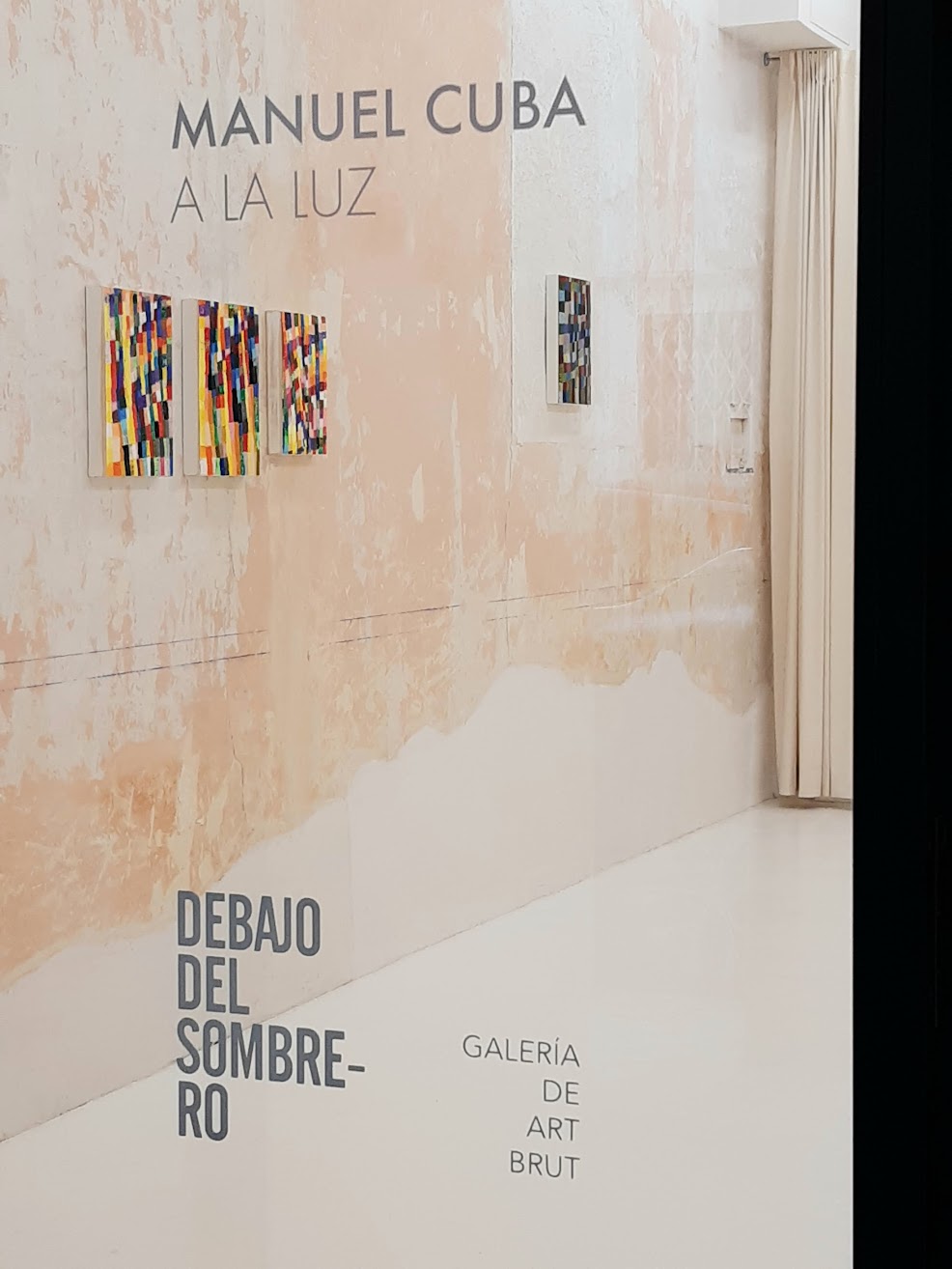

You have recently opened your own exhibition space. What does this step mean?

It is a very important step. The space is near Matadero Madrid, on Calle Alonso Carbonell, and combines exhibition, archive, and storage space. We don’t want it to be just the studio’s gallery, but a place that is attentive to what is happening in other assisted art studios around the world. There is no such space in Spain at the moment.

Tell us about Andrés Fernández’s project, which opened on January 23 at La Casa Encendida. Why does it stand out?

It is a site-specific virtual reality piece by the artist that will be on display for a year. What makes it stand out is that he is one of the studio’s most internationally renowned artists. He has exhibited at biennials such as Berlin, and his work has enormous power. It shows that these artists are not on the margins of contemporary art, but fully within it.

What projects are you working on for next year?

We are developing several important projects. Among them is an artist residency centered around the idea of home, which will be held at the gallery by London-based Palestinian artist Basel Zaraa, who works on the idea of exile. We will also be collaborating with the Spanish Embassy in Copenhagen, traveling with two artists, Andrés Fernández and Belén Sánchez, who will be doing two interventions in the space.

In addition, in our new exhibition space, we are planning our own exhibitions and contemporary projects linked to assisted art studios in other countries.

After almost 20 years, what dream do you still have for Debajo del Sombrero?

That it will stand the test of time. That it will remain a solid and stable studio, capable of supporting artists in the long term. That it will endure as a place where they can be, work, and develop their practice with continuity.

And on a personal level, what has this project given you after so many years?

It has given us so much and continues to surprise us. We have received enormous power, truth, and astonishing depth. They are enigmatic and deeply authentic artists. Rather than offering, we have learned to receive everything they have to say with attention and respect.

Written by: Beatriz Fabián

Beatriz is a journalist specializing in offline and online editorial content on design, architecture, interior design, art, gastronomy, and lifestyle.