We chatted with collectors Javier Lumbreras and Lorena Pérez-Jácome of Collegium

A few hours after receiving the A Prize for the Dissemination and Research of Contemporary Art through Collecting awarded by the ARCO Foundation, Javier Lumbreras and Lorena Pérez-Jácome tell us about the keys to the Adastrus collection.

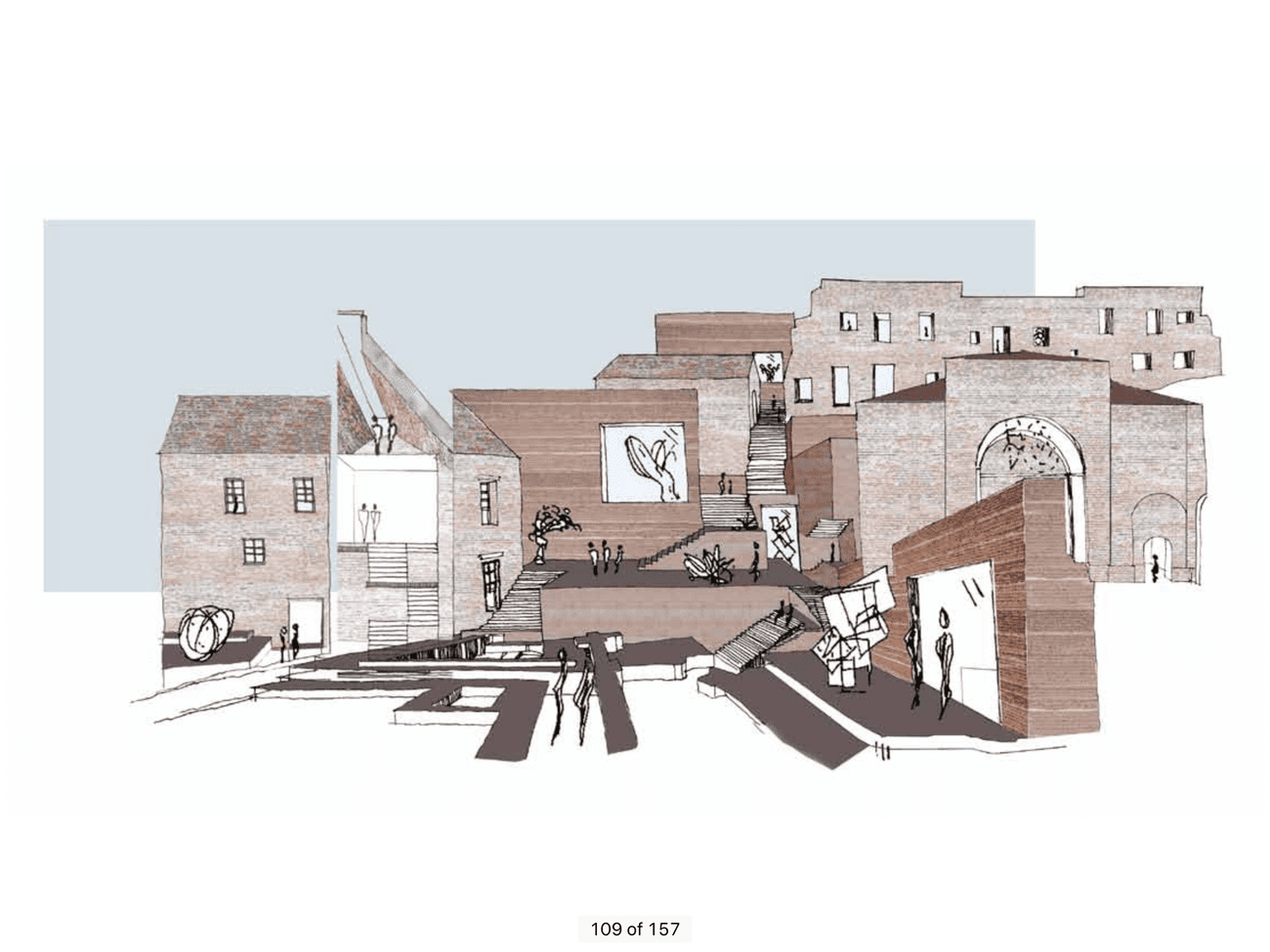

Javier Lumbreras y Lorena Pérez-Jácome plan to refurbish and create a complex of buildings in a former Jesuit monastery in Arévalo (Ávila) that will house Collegium. They will exhibit the Adrastus collection in this new museum and develop art dissemination activities.

The collection, assembled over three decades, gathers about a thousand artworks by more than 150 artists who traverse the perspectives of 40 countries and specific contexts. Each, in their way, dialogues with the urgencies of our global present. Roman Ondak, Karl Holmqvist, Nida Sinnokrot, Tomás Saraceno, Alicja Kwade, Wilfredo Prieto, Jim Shaw, and Abraham Cruzvillegas are just some of the names on the long list to which they want to add more recent acquisitions, such as the works of Regina de Miguel, Teresa Solar, Belén Rodríguez, Álvaro Urbano, Pep Vidal, and Marc Vives, which form part of the current exhibition ¡Doblad mis amores! Curated by Chus Martínez, it is open to the public in the church of San Martín de Arévalo until the end of March.

Why is the collection called Adastrus?

It is the name of a Greek demigod. We intended to find a name that connected with the idea of collecting as an activity that requires a lot of discipline, effort, and research, and hence the name, in the sense that he is the one who perseveres and who keeps at it.

This is undoubtedly an ambitious project; how did the collection begin to take shape?

The origin goes back to the 1980s, and although my first steps as a collector were in Spain, the first time I bought intending to collect was in 1987, already living in the United States. It is a series of drawings by the artist Heriberto Mora, with such dramatic titles as ‘La rata que canta’, ‘Hombre al acecho’, and ‘El Pozo,’ which I still have. It was the first time I felt that an emotionally charged “thing” was a little treasure, and I wanted to keep it. So it began as many collections usually start. In fact, I began to buy works with which I had a very intimate relationship that had to do with the way I thought, with emotional challenges, or with subjects I was curious about and wanted to explore. Art expresses what cannot be told in any other way or conveys the deepest part of the human being by the shortest route.

Collegium was born as a center for education, research, and experimentation in contemporary art. How did the origins of the project begin?

The museum project began to take shape after 2000 when the collection focus was reinvented due to our marriage. We discovered that our artworks could be a great tool to bring change and progress. As a result, we began to collect with a vocation of being useful and a purpose framed within the sphere of public service.

How do you think an art collection serves a purpose?

Let’s start by talking about the Guggenheim effect. It has to do not only with the domino effect that generates social, economic, and sometimes even political change, but the most important thing happens at the level of education. When you start to see that art reaches people who might not have thought of thinking differently. Art builds bridges, opens new paths and perspectives, and you find other possibilities. It’s liberating.

How did showing your private collection to the public come about?

There came a moment when we started to think about the idea of bringing it together in a space and, as a collector, you consider various options, from lending it to museums so that they could manage it globally or partially to donating it to an institution and, the third option, was to start up our own space where we could feel the great satisfaction of seeing the finished work.

Where did you choose to locate the collections?

Building a collection is almost eternal, and you wonder where to stop, so we set out to activate a space in a rural environment and not a big city because we are all center and periphery.

We thought of Miami, New York, or Veracruz, where Lorena’s family is from. But her grandfather was from Soria and, therefore, Castilian. Suddenly this Jesuit monastery in Arévalo came up, and something clicked. As you are always looking for a consensus, we invited some museum directors, gallerists, artists, and curators to get to know the site and give their opinion.

How do you see art from your philanthropic perspective?

Thirty-seven years after the purchase of the first piece of art, that series of drawings, as I reflect in the book The Art of Collecting art (2010), art and artistic work have a philosophical basis. It has also marked me to meet Arthur C. Danto, theorist of the philosophy of art of the 20th century and one of the great recent thinkers, famous for his thesis on the “end of art” and, Lorena and I have talked about it a lot, we’ve worked with professionals, and we’ve been pouring our broth.

Why did you choose the location in Arévalo, where your family is from?

One day a former mayor of Arévalo invited me to visit this space to consider it a possible destination for the collection. Even though it was a ruin, thanks to an agreement with the Junta de Castilla y León, we have managed to consolidate the dome, which was about to fall and which would have meant the disappearance of the San Nicolás church, formerly the church of Jesus, because it was part of the Jesuit school, also built by a patron of the time in 1585.

Who is carrying out the refurbishment work?

We talked to several architecture studios, but we chose the Mexican architect Tatiana Bilbao who has been working on it since 2012. What I liked about her is that her family is originally from Spain, and I felt she wanted to give back and leave a footprint. Most importantly, she has a sensitivity that made her take time to travel to Arévalo, dance the “jota,” or eat suckling pig, to soak up the environment and be able to create her architecture, which is what she calls “the architecture of others.” She is as if she were a medium who is impregnated with the customs and feelings of the local people to achieve projects that are sensitive to the community and not invasive.

That is why her project blends in with its surroundings; it is open to the city, it does not respond to a totemic structure, nor is it an illustrated museum where you arrive to be given lessons and leave beaten up, but instead it invites you to go in and out, to walk through the nooks and crannies, it is meandering, you go up and down six floors but, in reality, it is the element of surprise, you can get lost in it. It creates a very intuitive movement so that when you come across the works of art, you say wow! It moves your inner fiber simply by guiding you by intuition without prior preparation.

How do content and container interact?

Contemporary art is sometimes inhospitable on an emotional level, and we were thinking about what elements we had to improve that experience. One of them was architecture, and putting architecture at the service of the experience is Tatiana Bilbao’s achievement. Moreover, she carries it out with absolute independence.

What are the other pillars on which this new museum is based, apart from Tatiana Bilbao’s architecture?

On the one hand, there is Patrick Charpenel, a collector who has been and is a great friend and believer in the project. He gave it the form of a collection from his point of view as curator and director of the El Museo del Barrio in New York.

The third pillar was the foundational part of our project as collectors. Finally, the fourth pillar is Alfonso Alfaro, an ethnologist, philosopher, and disciple of Michel de Certeau and Michel Foucault, who gave it the profound philosophical underpinning that will help us to build identity.

When is Collegium scheduled to open?

There are no opening dates; right now, it is a titanic project that requires the complete recovery of the ruins that make up the complex and the incorporation of new buildings. For a year and a half, archaeological excavations have been carried out, and many objects that are now in the Museum of History of Avila have come to light. We intend to keep the ruins visible because it represents the footprint of time. Furthermore, it is a way of creating awareness, and coexisting with new buildings will lead to a complete experience.

It is intended as a single being. However, we have to be realistic and adapt the construction of this building to the uses and responses of art lovers who want to enjoy it and live in it emotionally.

Is Collegium already offering activities, and is it up and running?

The project is already up and running. The “Open for Works” program is active in the adjacent Church of San Martin, which hosts two significant exhibitions annually. So we decided not to wait for the construction to be completed. Last year, during the week of ARCO, the first exhibition opened, curated by Patrick Charpenel, which established a conversation between a series of engravings on Goya’s Caprichos and the work of 17 contemporary artists in the context of a baroque church.

Thus, the program got off to a very high start and was very well received in all circles because, in Spain, Goya is part of the identity.

I

In September 2022, Collegium launched the first edition of its program of residencies for artists in collaboration with the Inclusartiz Institute. So how has the experience been?

This year artistic residencies have already taken place. Chus Martínez has been the curator of a fascinating exhibition entitled ¡Doblad mis amores!, with six young contemporary Spanish artists coinciding with the week of ARCO. It is a program that is already underway and that will develop organically.

What differentiates this collection or this museum from other museum projects?

We realized that the collection had become a tool. Undoubtedly, in the 21st century, there are examples of ‘kunsthalle’ or exhibition spaces that work well without a permanent collection. It happens in Germany, Switzerland, in the United States. Still, for a museum to have that emotional link with the community, a connection with the citizens, it needs something to take care of and safeguard.

You consider Collegium to be a living organism. How does it interrelate with the public?

In reality, the whole project has come from below; this is everyone’s museum, and it wants to make people feel part of the project and let them know that it is theirs.

The current exhibition, entitled ‘Doblad mis amores’, establishes a relationship at all levels, from the people of the town who have nothing to do with art to those who like it very much. It says something to everyone because it is made from an emotional approach and tells stories. Martínez weaves it as a story and takes you by the hand, like in a tale, which appeals to childhood, the past, and emotion.

For all kinds of art lovers, it’s a welcoming space. But it doesn’t tell you how it is possible that you don’t know the names, this is the art, and you can experience it. The crux of art is that it generates emotions, opens doors for you, and generates thoughts that generally aren’t thought of.

After that more personal stage in which the collection begins, how do you choose the pieces that will make up the collection?

After the initial, more personal process, the collection draws a line in the year 2000, so that one of the conditions is that the artist has not had a monographic or retrospective exhibition before the year 2000, thus leaving aside the unattainable values of the 20th century. Secondly, as we wanted to build a representative collection of 21st-century art, all the works are dated to the present century.

Based on these two premises, we tried to look at different fields of science, mathematics, ethnology, and more. For this reason, many works appeal to a universe of circumstances. The universe of art is ‘too big to tame,’ that is to say, it is too vast to explore. You can reach all the abysses of existence, but you have to go little by little.

The veteran Ibero-American art platform Arteinformado finds itself in the context of its foundational aims. What does this initiative consist of?

For us, it is crucial, and it has a sense that fits perfectly with the vocation of the collection because Collegium is a center for the production, research, and experimentation of contemporary art. Still, there are also artist residencies and workshops, and we aim to recover the old crafts. It is a center where we pursue building knowledge and community. That is our aim.

Arteinformado is the most important archive of Ibero-American art of the 21st century. This is the only platform that manages this level of depth and information. That’s why I spoke to its creator Carlos Guerrero and proposed doing something with this mighty and extraordinary archive, which is also an essential means of communication. With total generosity, he has given it to us to promote its growth, activate art criticism, change its image, and continue to provide it with content.

How do you understand philanthropy in art?

Philanthropy is about being useful to others. I often say that collecting in Spain is scarce, rancid, and cowardly. But, in the case of Guerrero, he has had great courage and generosity. The Spanish are very generous; however, in art and philanthropy, it’s another matter. Something is going on there that doesn’t work, and let’s see if we can help take a step forward and unblock these archaic structures.

How do you feel about being called patrons or philanthropists?

They are very high-flown words. If we could invent others, it would be better, but at the expense of another definition, we’ll stick with this one; what can we do? They are necessary to communicate our project.

What made you decide to restore an old building?

The recovery of historic buildings is essential, and we are interested in not losing or disappearing all that human footprint that is a witness to history. But in addition, to do it in a Jesuit complex that was the first pedagogical project to be globalized and internationalized also struck us at the heart of the knowledge. Collegium was born with an educational vocation to teach what art is through evolutionary processes to delve into emotional knowledge as a counterpoint to scientific knowledge and AI, as a balance in which the museum becomes a platform of resistance against dehumanization.

To use another Mexican expression, a museum is a place where you can find the comfort and ‘apapacho’ that is like the embrace of the ¡Doblar mis amores! that is the exhibition of Chus Martínez. So therefore, we want to double our affection, double our love for one another.

You have created a program of artistic residencies. What does it consist of?

The program is called Entre Tiempos, and we at Collegium have set it up in collaboration with the Instituto Inclaustriz as an initiative that promotes the circulation of artists in the city of Arévalo and its surroundings and encourages research into themes related to the history, culture, and traditions of the region.

It was inaugurated between September and December 2022 by the Brazilian ceramist Ayla Tavares and until March by the indigenous artist Xadalu Tupã Jekupé, who lives in a Guaraní community in the Amazon and seeks to recover an erased part of his identity through his pre-Columbian roots. These residencies are very important for building bridges, for us the whole theme of Ibero-America is essential, and with Arteinformado, we are going to maintain it because I believe that all the knowledge that brings us closer to these cultures enriches us and encourages us to build together.

Have you acquired any artwork at ARCO?

Yes, the truth is that the collection had a very voracious moment of acquisitions, and now we are more focused on the museum project. However, as one of the things we hadn’t done before was to collect contemporary Spanish art, we are in the process of acquiring the pieces that make up the exhibition ¡Doblad mis amores! Curated by Chus Martínez and inspired by a quote from the poet Ramón Llull. It includes six projects designed by Teresa Solar, Álvaro Urbano, Pep Vidal, Marc Vives, Regina de Miguel, and Belén Rodríguez for the church of San Martín and, as a first-round,’ it responds to our intention to go deeper into the collecting of emerging Spanish artists.

Is interest in art and architecture growing nowadays?

There is still a great distance between public and contemporary art, much more so than for modern art. People more distant from the art world are now beginning to understand artists like Picasso. A hundred years have passed, or they understand Velázquez because centuries have passed.

In contemporary art, there is often a clash and even a confrontation. You have to make an act of faith; for example, the ‘core’ of our collection is very conceptual, complex works that you have to get your head around. As Saint Ignatius of Loyola said that art is not for the mentally lazy, I say this to provoke curiosity.

I sense that in a rural environment like Arévalo or Castilla y León, people don’t want to be left behind. Suppose we offer them these tools so that they can decipher art themselves. In that case, we will achieve that powerful social cohesion that keeps societies active to achieve happiness and longevity. That is why, in the rural environment, it is necessary to generate that interest and those social stimuli so that they feel that curiosity for art and do not leave the villages.

Editor: Beatriz Fabián Brihuega.

Photographer: Nieves Díaz.

Assistant photographer: José Antonio Gil Sánchez.